Wasn’t it Einstein who defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”? On Friday my twitter feed lit up with news that the UK government had “announced the creation of a national language centre and nine schools that will lead language hubs in a drive to improve the teaching of Spanish, French and German”… sounds great doesn’t it? And they are throwing £4.8 million at the initiative over the next four years, with the aim of “raising standards of teaching in languages”… all very positive so far, right? In addition, it seemed this was an evidence based proposal coming from “recommendations made in the Teaching Schools Council’s Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review led by headteacher and linguist Ian Bauckham.” I was genuinely feeling very optimistic and excited about this… until I clicked the link that is.

Let me be clear, I am not from the UK, I have never taught in the UK and I do not live in the UK. So why am I bothering to write this blog? Well, I work in an international school with many British teachers, parents and students. I have a large group of teacher friends who are British and my girlfriend is also British. I am also completing a Doctor of Education programme at the University of Bath in the UK and there is a strong likelihood I will teach in the UK at some stage in the future so their language education policies are important to me. From numerous conversations with Britons of all ages, it seems languages are taught, for the most part, in a very similar to way to how I was taught and how many teachers continue to teach.

In the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review that underpinned this big announcement, there is a distinct focus on continuing down the road of old school grammar and vocabulary teaching. Yet there is also references to students becoming demotivated and disinterested. Let’s just put this straight out there and say it clearly: these two concepts are closely linked. In my 11 years of teaching, I have chatted to hundreds of students and parents, and they say the same thing my classmates and I said 20 years ago when you ask them about their language class… it’s boring! It is just fill in the blanks, vocabulary lists, worksheets, grammar tables and stilted, forced “talk to your partner” conversations about ‘Pierre from Paris who likes baguettes’. Yes, there are some students who like learning this way but the vast majority are bored stiff and only keep going with the language as they perceive it as useful or their parents tell them it will be useful one day. The sad thing is that it does not have to be this way.

I was one of these textbook, grammar table and vocabulary list teachers too but then I discovered teaching with “Comprehensible Input” (CI). It is a well established theory of language acquisition, coined by Dr Stephen Krashen. Dr Krashen’s work does not feature in the appendix of the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review, and the word “comprehensible” is not present anywhere in the 27 page document. Yes, like everything in the world, it has its critics but those critics are certainly not my students, or the students of the thousands of CI teachers (and growing rapidly) around the world. This is not just some passing ‘fad’ or ‘method’. More and more teachers are converting to CI teaching as they see the incredible achievement and fluency it fosters but more importantly, their students now love their classes and their teachers love teaching them.

Some (not an exhaustive list) of the fundamental principles of CI are:

- Students require vast amounts of input (listening and reading) at a fully understandable level in order to acquire language; yes, we do modify and slow our speech to the level of the class so that it is almost 100% comprehensible by everyone at all times.

- The input is planned and taught in a way that is ‘compelling’ to students. They become so immersed in listening intently to what is happening that they acquire language without even knowing it.

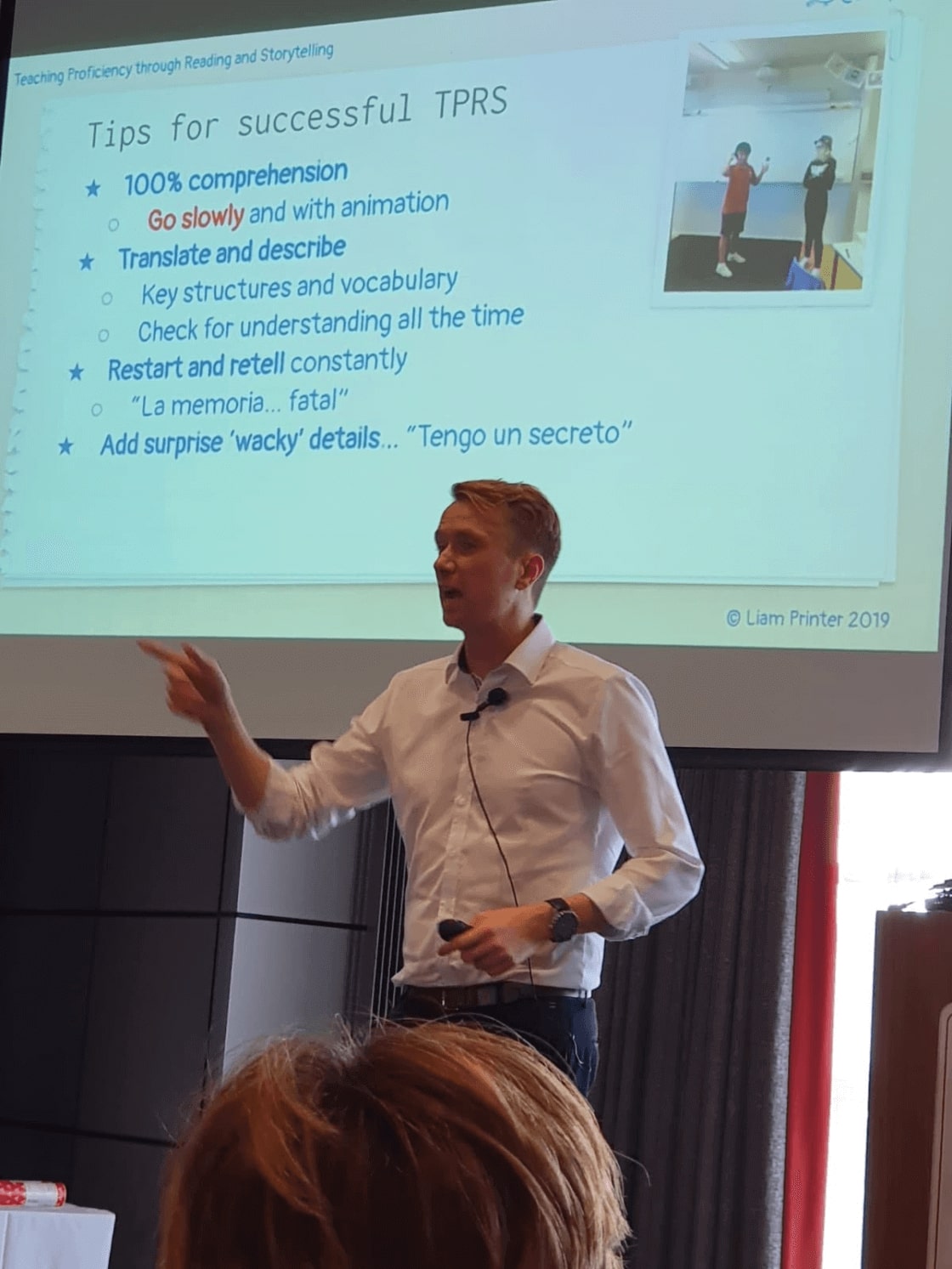

- For this reason, we teach with stories (both ones invented by the class and other fables and tales). A key ingredient in the CI mix is ‘Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling’ (TPRS); where students and teachers co-create a fun story together (more on this below)

- Students’ personal interests and their lives are the centre of our input; we are always looking for ways to include things about them in what we say and what they read.

- We do not shelter grammar: teachers speak using natural conversation and do not only use, for example, present tense in the first year. We do not, however, go into long grammar explanations but maybe give short “pop up” explanations if required.

- We do shelter vocabulary: no more long, useless lists to memorize which are organized by chapter in a text-book. I see words in vocabulary lists of text-books aimed at Level 1 students that I (as their teacher) have never seen before or if I have, I certainly can not ever remember actually having to use it.

- Instead students get lots of repetitions (through reading and listening) of the most common and frequently used structures in a language for communication; for example, “there was, we went, I saw, he has” etc.

- No forced output: students are not forced to speak and write before they are ready, after lots and lots of comprehensible input. Patience is crucial. The output will come and you will see that the less you force them to speak to more they want to speak.

I can already see some language teachers who are unfamiliar with this shaking their heads and saying “that would never work”… but it does. While the research around TPRS is still limited, it is growing. Karen Lichtman’s overview of all the current TPRS research shows that students achieve very highly when compared to traditional methods. In fact, 87 of 88 of my students mentioned "stories" as one of three things that helped them learn most in their end of year feedback surveys last year.

More importantly though, for me at least, is that both students and teachers find it to be highly motivating. My own doctoral research with the University of Bath focusses on this ‘motivational pull’ of teaching and learning languages with TPRS and the data is overwhelming: Students love learning with TPRS. As Stephen Kaufman of LingQ pointed out so aptly in his tweet “Unfortunately too few language teachers recognize that the role of the teacher is not to teach the language, but to motivate the learner to learn the language.” We all need to remember this. If you focus on the motivation, the students will do the learning and acquiring themselves. TPRS gives you a tool that will motivate your learners and they will come to class in eager anticipation. As one student said in my research study about learning through stories:

TPRS is just one piece of the CI jigsaw. There are loads of other ways to get the vast amounts of comprehensible input, that students need, in to the class like Movietalk, one word images, picture talk, star of the week etc but the aforementioned principles stay the same.. and you’ve got to admit, it makes sense, right? We are all language learners, we have learnt and are fluent in at least one language already so we know we can do it. But how did we ‘acquire’ that language as we certainly didn’t learn it? Well, we listened and were read to for about two whole years before we ever felt ready to start to say some of those words. We certainly didn’t start off learning about adverbs, conjunctions and the irregular verbs in the passé compose before we could even speak and read the language. Or if our parents did start us off learning that way, I’m not sure how much love or motivation I’d have for the language (or for them!) today!

Yes, it is great that the UK Government recognize the importance of language learning and I applaud their consultation approach. However, I also implore the Minister for Education and the authors of the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review to do their research. Go and read about CI and TPRS. Talk to teachers and students who are using it. Be ready for some enthusiastic and motivated responses. If we keep teaching languages in the same boring way we will have the same problems with uptake and retention for years to come. The frustrating thing is that we have the one subject that we can literally teach, talk and read about anything we want as long as it is the target language. We have the scope to be the most loved and interesting subject in the school. Any language teacher can do this by embracing ‘Comprehensible Input’ teaching approaches and working to make the input we give, “compelling” to our students’ ears and eyes.