As a language acquisition teacher, we are tasked with helping our students write (as well as speak) accurately. We all know that feeling when we take up a piece of work and we see those errors that we feel like we have repeated a million times in class already! I am sure we also remember that feeling when we were a student: getting back a piece of work that we felt like we had worked so hard on, but it is covered in the teacher’s red pen. So how should we go about error correction and feedback then? How many errors do we correct? How do we ensure the feedback is meaningful and used to push the student’s learning forward, rather than so deflating that it pushes them back?

In short, the language acquisition research argues that most students can actually acquire only 3-4 new words or phrases per 1 hour lesson. Yes, that is all. By acquire I mean, the word or phrase is engrained in long term memory and recall. The same is true with error correction and feedback in writing. If you correct every tiny little mistake and missed accent, the student will only remember the ‘sea of red ink’ and it will do very little to develop their acquisition.

However, it is important not to forget the ‘outliers’; those students who, like us as their teachers, are linguists, grammatical nerds, who want to know every tiny error and why it is there. In my experience about 1 in every 20 students falls into this category. They are the ones who ‘ask’ about those sticky grammar points when you are mid-flow, sideways-laughing, at a funny part of a story. As you get to know them, you can and should correct all their errors but quietly explain to them that you are also a ‘grammar nerd’ and you knew they’d want to understand why the direct object pronoun is placed beside the indirect object pronoun. Then invite them to a ‘geek out’ at break time and go over it in detail. They will feel loved and fulfilled so now you can focus on the 99% who do not need or want that level of correction.

Ok so which errors should we correct?

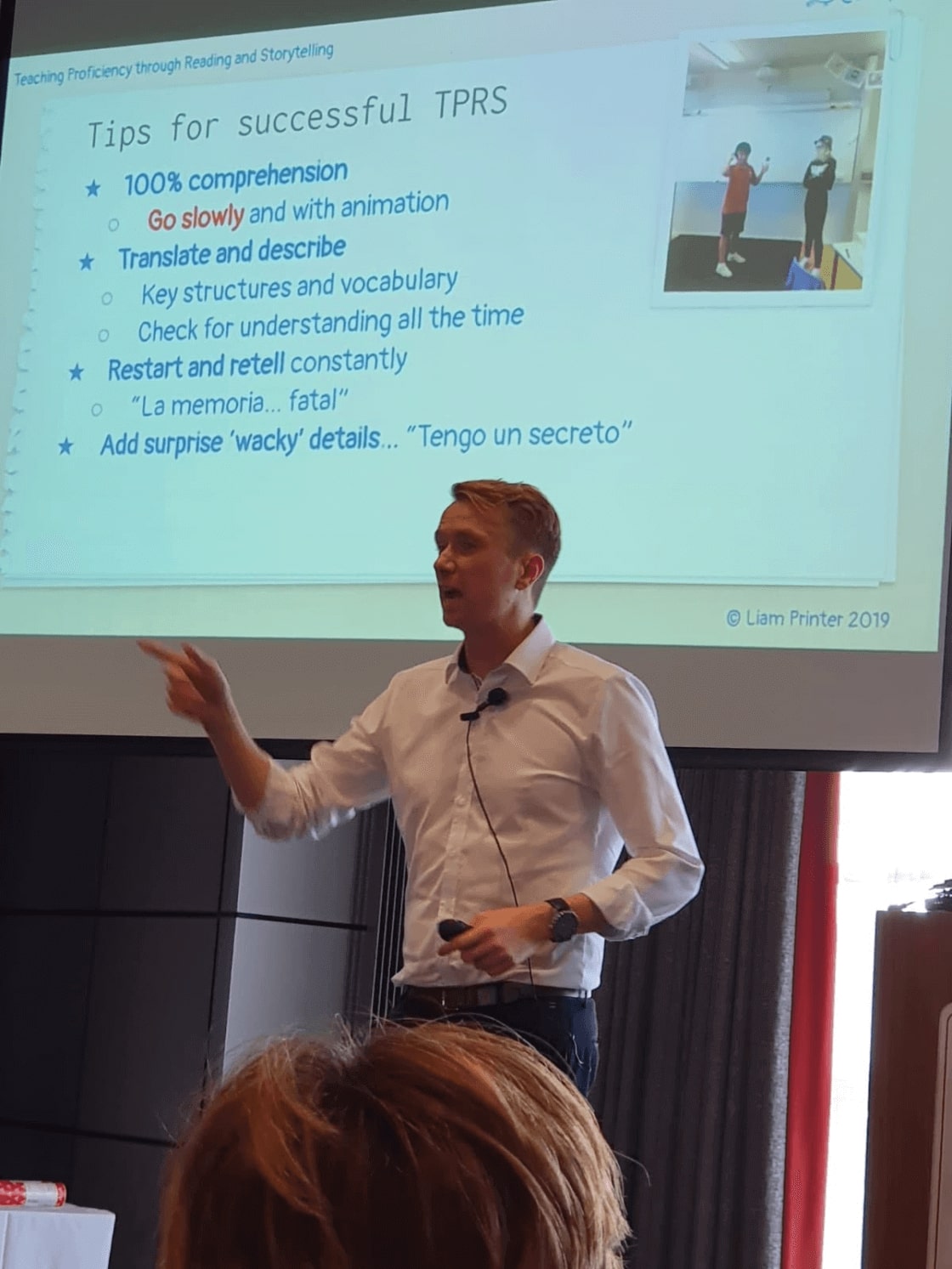

In the pictures below is a student’s re-write of a story we were doing in class. This is a 13 year old student who has just started her second year of Spanish. The writing was done under exam conditions in class (ie. with no help from computers, dictionaries or teacher) in ten minutes. We had been co-creating the story together for about 5-6 lessons.

As you can see, I choose not to correct all the errors. Instead, I focus on the errors that were vital to our story, or that were part of our ‘target structures’. For example “compró” (he/she bought) was an integral part of the story so I am correcting that. The difference between “quiero” (I want) and “quieres” (you want) has been a target structure in previous stories and at this stage, it is something I want students to be able to differentiate. However, in the first paragraph, I did not correct spelling errors like “una persona” or “difícil”. Why? Because they were not the focus of the story. From the research on intrinsic motivation, we know that students need to “feel” competent, that they can do it. If we correct every tiny error, the basic psychological need of ‘competence’ (from Self-Determination Theory) is dampened and the student feels like they ‘just can’t get it right no matter how hard they try’. I know it is challenging to let your red pen glide over an error which is glaring to you as the teacher but pick your battles! Does this error confuse the message? Was it a key focus in your lessons recently? If not, forget it. It will come later with more reading.

So what about feedback?

I like to use Geoff Petty’s ‘medals and missions’. It translates easily into Spanish and students immediately understand it. Pick 2-3 medals and 1-2 missions. Yes, you need ‘more’ medals than missions no matter how difficult this seems, you have to find them. However, and here is the kicker: in the ‘medals’ it is vital that you focus on the ‘process of language acquisition’ rather than the ‘quality’ itself. Praise the student with things like “I can clearly see you are reading at home” or “you are obviously listening intently in class”. That way, the student sees that they will be praised for going about the process in the correct way rather than just getting the answer right by whatever means. I only started doing this in the last year but I have seen huge differences once I reframed my feedback on the process and not product.

For the missions, I will usually give them a goal to improve the language like ‘use more description’ or ‘include connecting words to give your story more fluency’ rather than on the language itself. Sometimes, 1-2 short bullet points on a particular area of language is a good idea though. The students also use this ‘medals and missions’ way of giving feedback when doing peer assessment together in later tasks.

A further point that has really improved the way I give feedback is that I always try to read through the entire piece once before putting a single red mark on it. Yes, this is soooo difficult to do, it's like the red pen has a little red mind of its own at times! But if the piece is not too long, I try hard to do this. Then I ask myself: Ok, did I understand most of that? Were there lots of details from the story? Did it flow together? Has the student been listening to understand? It really focusses my mind on what is important and then allows me to pick out just 4-5 errors to concentrate on.

What happens next with the feedback?

For homework, students must write out their corrections. No ifs no buts. They write them always in the same place in their notebook so that all their corrections are together as they go through the year. We do this in a specific way:

- The student writes out the correct version of the sentence

- Next they use a different colour to underline or circle where the error used to be.

At the end they have a list of 4-5 sentences for each piece of written work that has a circle on the correct version, where they used to make mistakes. I always tell them this is the page to study or look over before any assessment. It is like having a teacher on your shoulder saying “psst.. remember, its quieres to say ‘you want’”. It means each student has a page of corrections that is specific and unique to them. I also encourage them to look over these corrections before they start their next written assignment.

Let’s be honest, grading and marking is not why we got into this job. It’s never going to be ‘fun’ but at least with this method, it is time efficient and focussed on improvement. Most importantly, it maintains student motivation. It prevents them from feeling like a failure as they will never again receive a page of red pen that deflates and destroys all their hard work trying to get it right. Have a go and let me know what you think! Or if you have a better or more effective way of grading then please share… I’m all ears!