August 2, 2024

Wasn’t it Einstein who defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”? On Friday my twitter feed lit up with news that the UK government had “announced the creation of a national language centre and nine schools that will lead language hubs in a drive to improve the teaching of Spanish, French and German”… sounds great doesn’t it? And they are throwing £4.8 million at the initiative over the next four years, with the aim of “raising standards of teaching in languages”… all very positive so far, right? In addition, it seemed this was an evidence based proposal coming from “recommendations made in the Teaching Schools Council’s Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review led by headteacher and linguist Ian Bauckham.” I was genuinely feeling very optimistic and excited about this… until I clicked the link that is.

Let me be clear, I am not from the UK, I have never taught in the UK and I do not live in the UK. So why am I bothering to write this blog? Well, I work in an international school with many British teachers, parents and students. I have a large group of teacher friends who are British and my girlfriend is also British. I am also completing a Doctor of Education programme at the University of Bath in the UK and there is a strong likelihood I will teach in the UK at some stage in the future so their language education policies are important to me. From numerous conversations with Britons of all ages, it seems languages are taught, for the most part, in a very similar to way to how I was taught and how many teachers continue to teach.

In the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review that underpinned this big announcement, there is a distinct focus on continuing down the road of old school grammar and vocabulary teaching. Yet there is also references to students becoming demotivated and disinterested. Let’s just put this straight out there and say it clearly: these two concepts are closely linked. In my 11 years of teaching, I have chatted to hundreds of students and parents, and they say the same thing my classmates and I said 20 years ago when you ask them about their language class… it’s boring! It is just fill in the blanks, vocabulary lists, worksheets, grammar tables and stilted, forced “talk to your partner” conversations about ‘Pierre from Paris who likes baguettes’. Yes, there are some students who like learning this way but the vast majority are bored stiff and only keep going with the language as they perceive it as useful or their parents tell them it will be useful one day. The sad thing is that it does not have to be this way.

I was one of these textbook, grammar table and vocabulary list teachers too but then I discovered teaching with “Comprehensible Input” (CI). It is a well established theory of language acquisition, coined by Dr Stephen Krashen. Dr Krashen’s work does not feature in the appendix of the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review, and the word “comprehensible” is not present anywhere in the 27 page document. Yes, like everything in the world, it has its critics but those critics are certainly not my students, or the students of the thousands of CI teachers (and growing rapidly) around the world. This is not just some passing ‘fad’ or ‘method’. More and more teachers are converting to CI teaching as they see the incredible achievement and fluency it fosters but more importantly, their students now love their classes and their teachers love teaching them.

Some (not an exhaustive list) of the fundamental principles of CI are:

- Students require vast amounts of input (listening and reading) at a fully understandable level in order to acquire language; yes, we do modify and slow our speech to the level of the class so that it is almost 100% comprehensible by everyone at all times.

- The input is planned and taught in a way that is ‘compelling’ to students. They become so immersed in listening intently to what is happening that they acquire language without even knowing it.

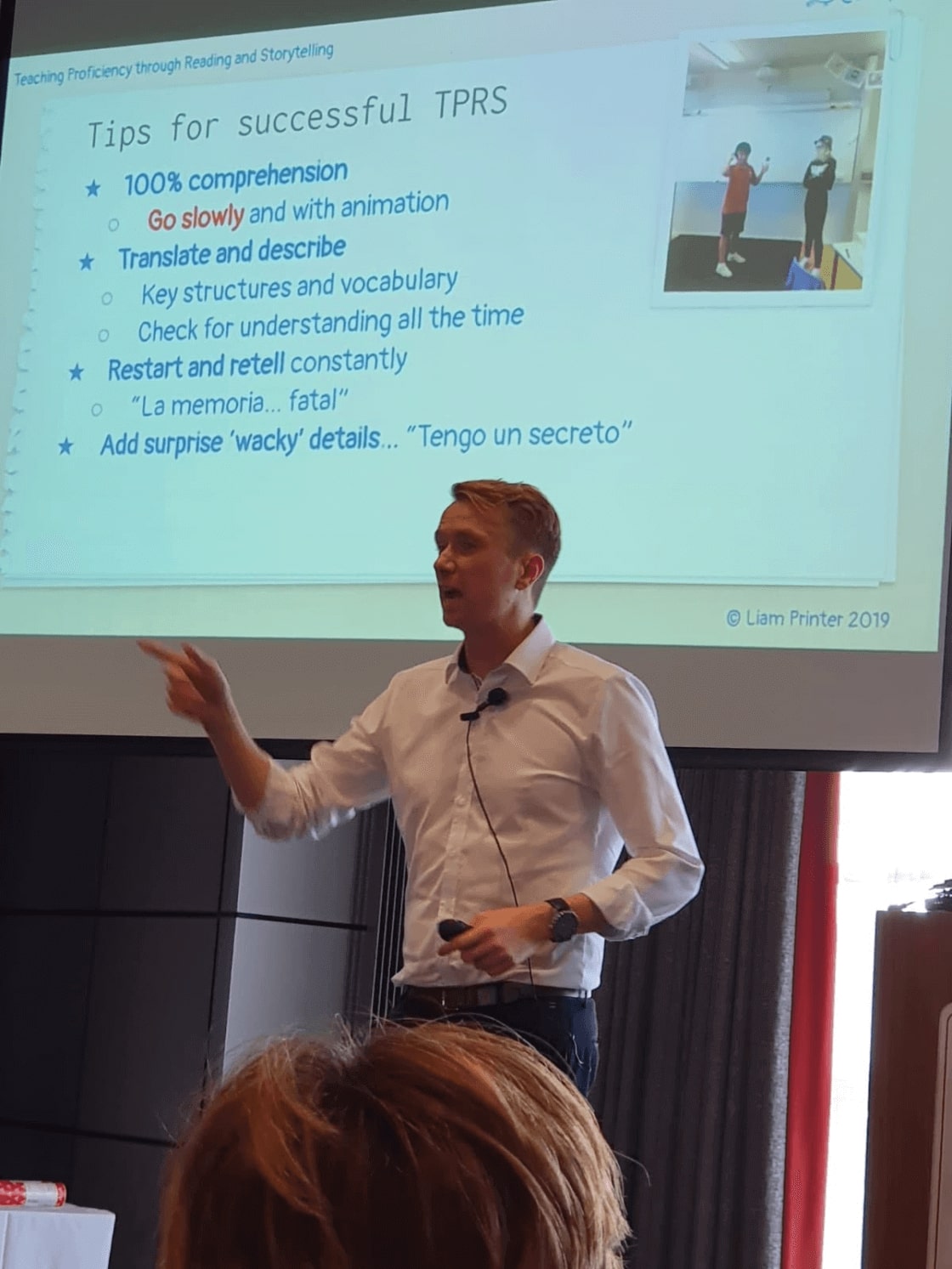

- For this reason, we teach with stories (both ones invented by the class and other fables and tales). A key ingredient in the CI mix is ‘Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling’ (TPRS); where students and teachers co-create a fun story together (more on this below)

- Students’ personal interests and their lives are the centre of our input; we are always looking for ways to include things about them in what we say and what they read.

- We do not shelter grammar: teachers speak using natural conversation and do not only use, for example, present tense in the first year. We do not, however, go into long grammar explanations but maybe give short “pop up” explanations if required.

- We do shelter vocabulary: no more long, useless lists to memorize which are organized by chapter in a text-book. I see words in vocabulary lists of text-books aimed at Level 1 students that I (as their teacher) have never seen before or if I have, I certainly can not ever remember actually having to use it.

- Instead students get lots of repetitions (through reading and listening) of the most common and frequently used structures in a language for communication; for example, “there was, we went, I saw, he has” etc.

- No forced output: students are not forced to speak and write before they are ready, after lots and lots of comprehensible input. Patience is crucial. The output will come and you will see that the less you force them to speak to more they want to speak.

I can already see some language teachers who are unfamiliar with this shaking their heads and saying “that would never work”… but it does. While the research around TPRS is still limited, it is growing. Karen Lichtman’s overview of all the current TPRS research shows that students achieve very highly when compared to traditional methods. In fact, 87 of 88 of my students mentioned "stories" as one of three things that helped them learn most in their end of year feedback surveys last year.

More importantly though, for me at least, is that both students and teachers find it to be highly motivating. My own doctoral research with the University of Bath focusses on this ‘motivational pull’ of teaching and learning languages with TPRS and the data is overwhelming: Students love learning with TPRS. As Stephen Kaufman of LingQ pointed out so aptly in his tweet “Unfortunately too few language teachers recognize that the role of the teacher is not to teach the language, but to motivate the learner to learn the language.” We all need to remember this. If you focus on the motivation, the students will do the learning and acquiring themselves. TPRS gives you a tool that will motivate your learners and they will come to class in eager anticipation. As one student said in my research study about learning through stories:

TPRS is just one piece of the CI jigsaw. There are loads of other ways to get the vast amounts of comprehensible input, that students need, in to the class like Movietalk, one word images, picture talk, star of the week etc but the aforementioned principles stay the same.. and you’ve got to admit, it makes sense, right? We are all language learners, we have learnt and are fluent in at least one language already so we know we can do it. But how did we ‘acquire’ that language as we certainly didn’t learn it? Well, we listened and were read to for about two whole years before we ever felt ready to start to say some of those words. We certainly didn’t start off learning about adverbs, conjunctions and the irregular verbs in the passé compose before we could even speak and read the language. Or if our parents did start us off learning that way, I’m not sure how much love or motivation I’d have for the language (or for them!) today!

Yes, it is great that the UK Government recognize the importance of language learning and I applaud their consultation approach. However, I also implore the Minister for Education and the authors of the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review to do their research. Go and read about CI and TPRS. Talk to teachers and students who are using it. Be ready for some enthusiastic and motivated responses. If we keep teaching languages in the same boring way we will have the same problems with uptake and retention for years to come. The frustrating thing is that we have the one subject that we can literally teach, talk and read about anything we want as long as it is the target language. We have the scope to be the most loved and interesting subject in the school. Any language teacher can do this by embracing ‘Comprehensible Input’ teaching approaches and working to make the input we give, “compelling” to our students’ ears and eyes.

I know, I know… as a ‘comprehensible input’ (CI) teacher, I shouldn’t ever really be teaching ‘verbs’ but bear with me. Like most other self-proclaimed CI teachers, I spend most of time focusing on giving students lots of understandable input through stories, personalized questioning, ‘special person’ interviews among lots of other strategies. However, after a few weeks doing this I often get a couple of questions and requests from students about the other forms of the verbs that we haven’t done yet. After hearing various verbs and language structures in context and using them in stories, a certain number of students will always want to see the whole verb written down so they can make connections and patterns to other structures they want to use. Once a few of these requests come in, I usually pick one entire verb that we have been using in the stories and ‘teach’ it through this activity.

Here’s how it would work. Let’s say we have been doing a story about food and restaurants using the verb ‘pedir’ to order. First, I will break students into teams and see if any team can write all versions of the verb ‘pedir’ in the past. They’ll usually get the ones from the story immediately and I might have to show them the other forms. Once we have all 6 subjects of the verb in the past tense they have 20 minutes to go and write a mini restaurant sketch using all 6 parts of the verb. This is where I love the atmosphere the stories create because they always come up with weird, wacky and wild sketches. It is a really great way for them to see that ‘pediste’ (you ordered) for example and ‘pidió’ (he/she ordered) are different and used for different people. I’ve found that many Anglophone students struggle with this as in English it is just ‘ordered’ for everyone.

The sketches really get them thinking in groups about how to include all parts of the verb and how to make it interesting. They then act it out in front of the class showing off the drama skills they have picked up in our stories.

If you want to make it even more fun, you can give a time limit of say 2 minutes for the acting of the sketch. Then have them all come back up and act it out again but each version they do, you cut the time limit in half. By the end they only have 15 seconds and will end up only saying the absolute key phrases in the sketch but which will undoubtedly contain ‘pedir’ in the past tense.

Zero worksheets, zero filling in the blanks, zero ‘rote learning’, zero confusion about which parts of verb apply to who through so many repetitions of a tough verb to learn, so many smiles, so much fun and so much acquisition.

During the summer, when reading ‘Creating cultures of thinking’ by Ron Ritchart, I came across ‘Individual Feedback Sessions’. In the book the teacher claimed that these sessions really helped him to foster long-term, meaningful relationships with his students that had a hugely positive impact on their achievement outcomes and also meant he never had Year 13 (equivalent to Grade 12 or the students in their final year of High School) work to mark at the weekends. Obviously, I want my students to achieve their potential and I also know that the research is pretty robust about the importance of building strong bonds and relationships in the classroom… but ‘no marking at the weekend?’, now that really made me sit up and listen.

In their final two years at our school, our Year 12 and 13’s are preparing for the International Baccalaureate final exams as part of the IB Diploma Programme. For Spanish B (language acquisition) this means they have approximately 12-15 different ‘text types’ that they must be familiar with as any can come up in the exam. In total, between the written assignment, and the written exam paper, their ability to write effectively in Spanish counts for 45-50% of their final mark. Whether I agree with that weighting or not, these are the confines, within which I teach. We would all love to just teach for the love of learning and not have final exams to worry about or prepare students for but that is simply not the reality for the vast majority of High School teachers. We have a responsibility to the students to prepare them for these final examinations whether we like it or not. Nonetheless, I am a strong believer in never allowing the ‘exam’ to dictate our classroom. I trust that if we get them motivated and loving the language, then achieving their own unique potential will come naturally and it will not feel like all we do is practice for examinations… but this is another blog post in itself!

Until this year, my Year 12 or 13’s would usually write a different text types every 2 weeks. I would take them home and read them, and then provide them feedback using Geoff Petty’s ‘Medals and Missions’ format. Before they handed in their work, they were required to fill out a ‘proforma’ which is essentially a self-evaluation that includes my two specific goals from the previous task. I always felt this system worked really well, the students said it was very beneficial and I saw a real difference in their writing over time. The proforma with my two goals gave them concrete objectives to work on, the self-evaluation made them accountable for following guidelines and the ‘medals and missions’ clearly highlighted things they did well and areas for improvement. However, the ‘proforma’ was often forgotten or left until last and only done in a rush on the day it was due. In addition, sometimes they clearly hadn’t read my objectives from the previous piece until it was too late, which was, of course, frustrating for me as the teacher given that I felt like I was spending a lot of time marking their work and writing their objectives, medals and missions.

In step ‘Individual Feedback Sessions’ (IFS) to the rescue. First and foremost, before you ask, yes they do take time and yes it would be a challenge to do in a very big class but after a month of using them, I’m convinced the time investment is worth it. Students still complete a ‘proforma’ but instead of handing this in with their written work, they bring it with them to their IFS along with a printed copy of their text type. The schedule for each student’s IFS is negotiated with the teacher in advance in order to find a time that works for everyone. No longer can there ever be any confusion about deadline dates and submission times for their work as it is always due during their IFS, which is at the same time on the same day every second week. As Spanish B texts are generally 400-600 words, my sessions with students are typically 10-15 minutes in length and take place during free periods if possible, or alternatively during break or after school.

The biggest change for me with this system is that I can already see a strong relationship and bond beginning to grow with individual students as you sit with them one-on-one and chat. In addition, it seems having to sit down beside the teacher and discuss their work increases their accountability too. They always have their text printed and proforma in hand as they know if they show up without it, then I have nothing to mark. I’ve also noted that my two specific objectives are being met more frequently, probably because they know I will be beside them reading their text and will immediately know if they haven’t done them.

There are some further, notable, spin-off advantages to this too. First of all, I never have any Year 12 or 13 work home with me in the evening any longer, it is all done there and then with the student beside me. In addition, the students themselves write their Medals and Missions while I sit next to them after we’ve discussed their work. Finally, and for me this is actually a huge benefit, they are getting 15 minutes of chatting in Spanish with the teacher one-on-one, which is also boosting their oral fluency and confidence. By the time those dreaded oral exams roll round they will be very comfortable and used to talking to me in Spanish.

If you have very big classes, you could do them with pairs of students but if possible I thoroughly recommend the time investment as in the long-term, it will be this strong relationship with the student that makes the difference.

Leaving my classes behind with tests and cover work is always a tough thing to do and to justify, especially when (as most teachers will know) setting and correcting cover work takes twice as long and is twice as much hassle as just being there and teaching the class yourself. Nonetheless, I always come away from educational conferences full of new strategies, bursting with ideas and feeling completely re-energised about teaching and learning. The Alliance for International Education conference in Amsterdam was no different.

The 3 day event kicked off with a keynote address by Prof. dr Marli Huijer, the first woman to become ‘Thinker Laureate’ of The Netherlands. Yes, her job is to think… to think and to discuss, to think and to problematise, to think and engage educators in debate about the issues facing schools around the world. Her address turned the popular idea of ‘travelling to broaden our horizons’ on its head and made us instead reflect on those who ‘stay behind’. Upon returning home for a visit, most of us teacher vagabonds are faced with questions like ‘so how much longer will you be away?’, yet at the same time, we hope that those who ‘stay behind’ will maintain and protect that culture we remember so dearly in its perfect unaltered state. Does this create a kind of deep, often unspoken, resentment on both sides? Are we trading a gain in global understanding for a loss in local familiarity?

A unique part of the conference is how it is divided into ‘strands’ based on the presenters and topics being put forward. As I was presenting my research on the motivational pull of teaching languages through storytelling, I was placed in the ‘role of language’ strand. Other strands included, ‘internationalising education’, ‘learning, teaching and pedagogy’, and ‘researching international education’ among others. This set-up allowed for rich and nuanced discussion with ‘like minded’, yet very different, people coming at the theme from various perspectives. Our ‘role of language’ strand included, for example, presentations from primary, secondary and third level, and encompassed issues ranging from ‘home language’ policy and support in schools, to innovative approaches to teaching, to how language can be used as a scapegoat for ability, to the intriguing Dutch bilingual education system. Truly fascinating, insightful and thought-provoking.

I learnt so much in just three days and I am thoroughly looking forward to sharing some of the ideas with our language department and administration at ISL but two things really stood out for me. Firstly, as language teachers we are lucky that we have one of the only subjects in the school where students can literally do inquiry based learning into anything as long as it is in the target language. We have endless freedom and autonomy and we need to tap into this and allow students to lead their learning through inquiry that compels and interests them, inquiry makes them want to speak about it rather than being forced to.

Secondly, borrowing from Terry Haywood whose addressed closed the conference, just as we update the systems on our phone so they can cope and work better, we must update the systems in our schools and language departments to meet the needs of the students, as it must be the students’ learning and interests that are always at the heart of our decisions. We are so lucky and fortunate to have multilingual students in our classes who speak a host of diverse languages at home, but are we really doing enough to nurture their home language and help them to maintain that local connection to their culture and language? The research tells us that a rich and deep understanding of the ‘home language’ aids cognitive and emotional development across the subjects but I fear our 'English-first' driven ‘international school world’ may be sadly transforming multilingual mastery into monolingual mediocrity.

The second keynote speech came from Dr. Conrad Hughes,

who challenged us all to look inside ourselves at our own deeply ingrained prejudices, as we all have prejudices whether we like it or not, and try to confront them. He left us all reflecting intensely on how these prejudices are maintained and fostered but also enlightened us with concrete strategies to unpick them both for ourselves and in our classrooms. Being in contact with those who come from places and cultures we don’t fully understand and working with them towards a common goal, thus learning the true meaning of ‘empathy’ is crucial.

I think above all, I left with a sense of hope and gratitude that I am in a job where I get the chance to make a real impact on the world every day through the young people I am in contact with. We are the ones, both us as teachers and our students, who have the ability and scope to change the face of modern international education. So enough with all the talking, now let’s get started.

Learning about Spanish food, tapas, traditions and all of the other amazing culinary aspects of Spanish life is part of most standard Spanish courses around the world, so how can we, as teachers, bring it to life for the students?

Well to begin with, we need a TPRS story of course! In our 'Foods and Culinary Traditions' unit I first started with a story about a man who wanted to eat 27 different tapas so he could become the 'Best Tapas eater in the World'. We circled the verb 'pedir' in various forms in the past as this can be a tough one, whilst also bringing in lots of new food and drink vocabulary.

Start with a story

Well to begin with, we need a TPRS story of course! In our 'Foods and Culinary Traditions' unit I first started with a story about a man who wanted to eat 27 different tapas so he could become the 'Best Tapas eater in the World'. We circled the verb 'pedir' in various forms in the past as this can be a tough one, whilst also bringing in lots of new food and drink vocabulary.

After the storytelling aspect students then spent a class coming up with a role play where 6 different people or groups had to use 'pedir'... for example, most groups chose a restaurant scene and had things like "Yo pedí gambas"... "No hermano! Tu pediste churros, mis padres pidieron gambas!"... "Qué ridículo!" etc. The students really loved this part and it was a lot of fun.

'Pinchos' making cook-off competition

The last day of term was arguably the best though... we had a 'Pinchos Competition'. Pinchos or Pintxos (In Basque) are smaller portions than tapas, and traditionally can be eaten in 2-3 mouthfuls. After a presentation and discussion on the the pinchos tradition, students had to invent their own pinchos and enter them in our 'Españoland Annual Pinchos Extravaganza'! I supplied the bread and the sticks and the students had to bring 3-4 ingredients to make the pinchos. They had 20 minutes to complete them and they also had to write a little sign explaining the ingredients and why they chose them. They were encouraged to link it to their own culture somehow.

We had some incredible creations and students then voted for their two favourites after tasting them and reading the signs. I also treated it a little like 'masterchef' and went around speaking to them and asking questions as they made their creations. They loved the idea of making something very cultural themselves and they were really immersed in the Spanish idea of sharing little mouthfuls of food together as a group.

It was even more 'authentic' thanks to another Spanish teacher and mother of one of the students in the school, coming in and giving us a demonstration of her own pincho using Spanish tortilla de patatas. Definitely something I am going to do again next year and of course I also had the benefit of tasting all the wonderful

I am exhausted but I am happy. I love TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) and see huge benefits from it but it does take its toll when you make the (probably incorrect) decision to do a whole week of it in every one of your 6 classes which are almost all at different levels! It was likely even more taxing this time too as I actively tried to put all the wonderful strategies and tips I received from Grant Boulanger at his 2 day workshop in Leysin American School last week.

Grant was fantastic and I learned a great deal from him in just two days. Here are some of his strategies that I implemented and will definitely keep as they worked so well:

- Student Jobs: I have my ‘ambassador’ who helps me get class set up and ensures I have 4 different coloured markers at the board, my ‘luces-puerta-ventana’ person who turns on and off the lights and closes or opens the door and windows and my ‘pizarra-papel’ person who distributes mini whiteboards and paper.

- Story Booklet: Grant has a student write the story in full in a notebook as it is unfolding in either English or Spanish depending on the level. Genius! It meant I had an immediate record of exactly what happened with each class.

- Take the answer with the most energy: I’ve often made the mistake of taking the response that ‘suited my vocabulary goal’ or my story but since the workshop I always go with whichever one gets the most energy from the class. This really helps them remember and it validates that students intervention.

- Homework reading to parents: I love this idea of having the student read and translate a story to their parents. So much learning going on and the parents get to see their child’s quick progress too.

- Gestures: I never used to work the structures in gesture format before the story began but I think this helped a lot of learners visualize what the structure meant. It’s staying!

- TPRS works for all levels: I spent a week in TPRS mode with my very advanced IB Diploma students circling difficult and complex grammatical structures and not only did they love it but the timed writing they did at the end of the week was some of the best stuff they have ever written.

There were many others too and lots of this comes down to your own personal style as a teacher. I also grabbed the ‘toro’ by the horns and threw all my desks out… just chairs with mini whiteboards to lean on - ‘a la Grant’ style. I am not 100% convinced on this yet, the students did seem to be more focused and concentrated but as the week went on and this became the norm and was no longer a novelty they managed to find things to distract their attention from the story. The jury is still out on this one.

One thing I wholeheartedly and 100% concur with Grant on is… TPRS is really REALLY fun for both the students and the teacher! You have the most amazing hysterical moments and personal connections with your students that quite simply make teaching a pure joy. Kids are great. They make us laugh all the time and when you give them creative license to invent parts of stories they will make your sides split. On numerous occasions this week I had tears rolling down my face from laughter and they were all in hysterics at me not being to speak because I was laughing so hard… tell me that is not a class you would want to come back to!