August 2, 2024

Many of the wonderful listeners of The #MotivatedClassroom podcast have been getting in touch to ask for examples of what students writing output looks like given that I focus primarily on lots of compelling, comprehensible inputs with little or no formal grammar tests or tasks, worksheets or vocab lists, particularly in first two years.

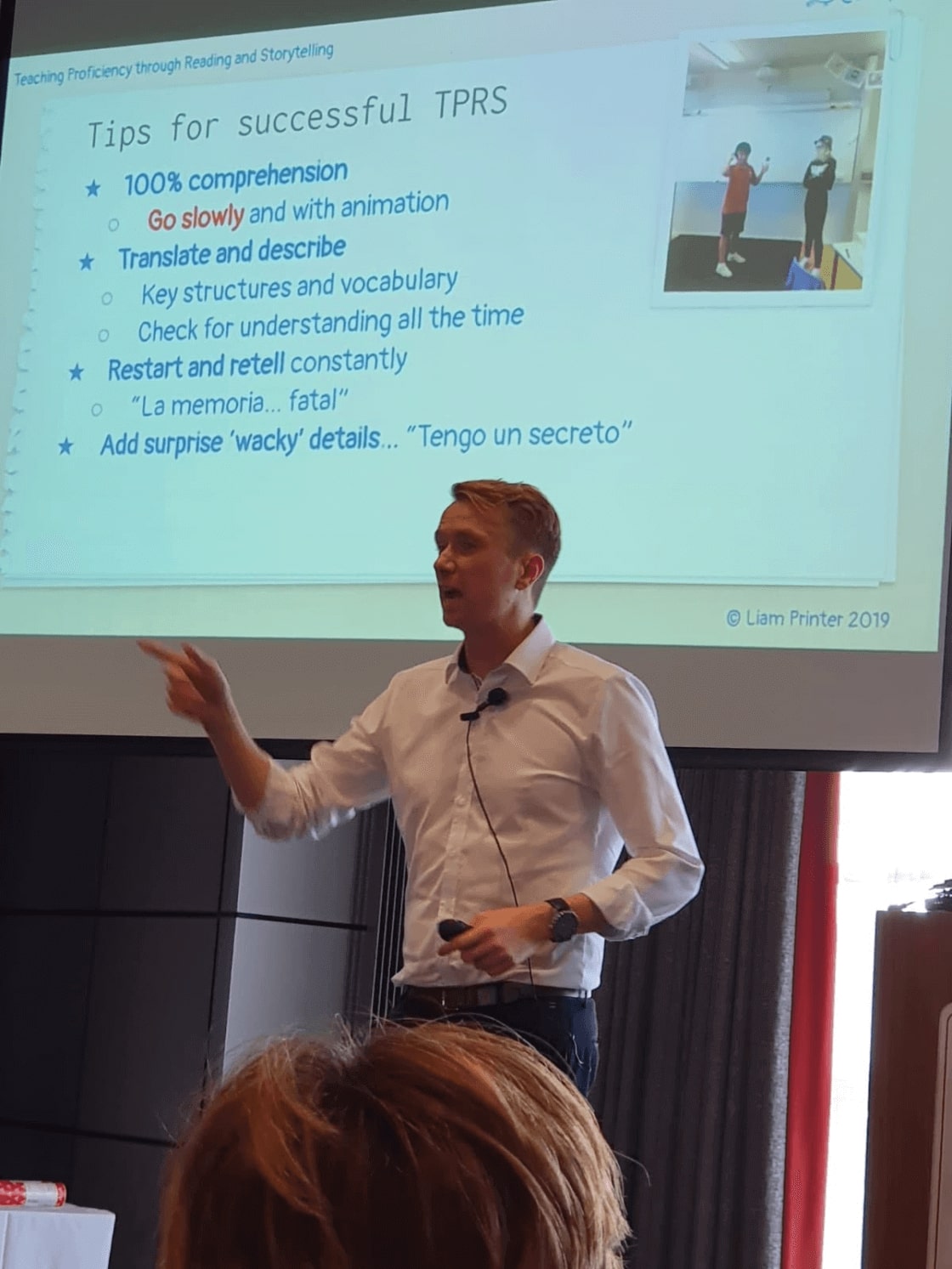

Below are some examples of my Spanish Year 9 students 'timed write' from April this year. This is a mixed ability class (no high/low sets or streaming) of students who were mid way through their second year of Spanish with me. They are 13-14 yrs old and in total have had 1.75 years of Spanish. Each week they have four 45 minute lessons of Spanish. After one week of doing a TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) co-created story with them, at the end of the fourth class class I asked them to write as much as they could remember of the story in 5 mins. They had no prior warning, no studying beforehand, no memorization tasks, no drills or worksheets. They had just been immersed and involved in the story creation for a week with me. The story is typically 'asked' in short 5-10 minute blocks, then students will interact with it by drawing scenes and retelling them to their partner, answering questions from the teacher, miming scenes and discussing, reading back on it with images etc. Then the plot continues and they are intently listening to see what happens next whilst also providing ideas for the details in the story, as well as some of the more extroverted students are helping me by acting it out.

After exactly 5 minutes of writing their 'timed write', they stop. There is no correction of mistakes or individual feedback on this writing. Accuracy is not the goal. The goal is fluency, competence, proficiency and confidence. So, they just count the words to see how much they were able to write from memory of their own co-created story. They are often shocked and pleasantly surprised by how much they can write with no preparation. As the teacher, I read through them all very quickly, looking for common, collective errors and use these to inform my teaching for the upcoming classes. If many students have not mastered one of my key structures, then clearly they need more repetitions of it in the next class, more personalised questions about their lives, more inputs.

Although tempting to only post the 2-3 best examples (as I have done in the past!), for authenticity this time I selected a random range of 11 examples from a class of 24. Through this range of exemplars I wanted to show you how a story can be internalised, acquired and 'learned' by all students; how stories reach all learners and just those we consider most motivated or driven to succeed. For the Spanish teachers reading this, my target structures with this story were "siempre ha querido; nunca ha probado; aún no ha logrado" (has always wanted; has never tried; still hasn't achieved). While I have my skeleton script idea of how the story will progress, it was the students who contributed the names, places and details while acting it out. This raises their autonomy. They feel ownership over it. They feel they created it. They feel it is "their" story. So they remember it and can re-tell and write it with no prior practice activities. Sure, there are some errors. Of course there are. Accuracy and grammar form are not the goal here... but they are a very pleasant by-product of compelling inputs and intent listening! The goal is confidence, fluency, proficiency, enjoyment and motivation for Spanish. Worksheets and grammar accuracy can come later, once they have listened to and read loads of compelling, comprehensible, input first!

In these early stages, the first two years in particular, we do not need to 'drill' outputs for accuracy. It is the interesting, compelling inputs through stories that lead to the proficient output from all learners and not just some! There is a different, more engaging, more creative, more fun and more enjoyable way to get to the same end goal. Think co-creation, not regurgitation. Think autonomy, not monotony. Think engagement, not detachment. Think motivation, not examination.

What do you think? I'd love to hear your comments! Download the weekly episodes of The Motivated Classroom podcast to listen to more research based teaching discussions about raising motivation in the language classroom.

Enjoying The Motivated Classroom Podcast? Leave a quick review on Apple Podcasts or join me on my patreon page here. I'd love to hear from you. Get in touch on social media with your questions and comments using #MotivatedClassroom via the channels below:

- Instagram: @themotivatedclassroom

- Twitter: @motclasspodcast

- Facebook: themotivatedclassroom

After 22 episodes and over 670 minutes of content, The Motivated Classroom podcast is taking a short, but much needed, two week break! For those who have fallen a few episodes behind, this winter break gives you a chance to catch up on all those episodes that have been bookmarked in your podcasts app for the last few weeks of this crazy semester! Episode 23 with Adriana Ramirez, will be released on Friday 8 January 2021.. So not too much longer to wait!

As my first venture into the podcasting world, it has been a steep learning curve in creating, recording, editing and promoting the content… but all things considered, I’ve loved it! Unbelievably, the podcast has now hit a whopping 21,000 downloads since it began five months ago at the end of July. Mind. Blown. Never in my wildest educational dreams did I think it would have been listened to so many times so quickly. Of course, there is no way people would find and listen to The Motivated Classroom podcast without the help of all of you wonderful listeners. I am hugely grateful to all of you for liking, sharing, telling friends and spreading the word. I want to say a special thank you to the 15 people who have become patrons of the podcast on my patreon.com page. I am indebted to your kindness and really appreciate your generosity! I’ve enjoyed some lovely coffee and crisps thanks to all of you!

Episode One, “Motivation: What is it and how do we do it?”, remains the most popular episode of the series, recently passing 2000 listens on its own but I think my favourite episodes have been those where I had the chance to interview some of my heroes. I want to take a moment to share my deep gratitude with those educational icons and legends that joined me as guests on the podcast this series: Soukeina Tharoo, Joe Dale, Beth Skelton, Chloe Lapierre and Adriana Ramirez (episode forthcoming); Thank you for sharing your passion and in-depth knowledge with the listeners. I loved chatting to you all and I learn so much from you each and every of you, every time we talk. Go raibh mile maith agaibh!

When I started my Doctorate in Education back in January 2015, I guess some of my main reasons for undertaking such a monumental project were; to improve my practice, to learn more, to challenge myself, to engage with research and potentially to open some doors and potential career prospects. What I didn’t know or expect at the time, was that by the time I would be finishing it in late 2020, a major objective would be to somehow share and disseminate both my own research findings and those from other major studies that were impacting my classroom practice. I wrote some articles, presented at conferences and led workshops but it wasn't until a good friend said “you should start a podcast about all this stuff” that I felt like other teachers were genuinely beginning to benefit from the research I had done and read about. Now, after five months and twenty-two episodes, it is clear that so many teachers around the world are really connecting to the motivational research and it makes my day to read the messages and emails from people saying they tried some of the activities in class and the students loved it.

So, thank you, merci, gracias, danke, obrigado, dank je and go raibh maith agaibh 🙏! I’d love to hear what episodes you liked the most so drop a comment here, post on The Motivated Classroom facebook page, comment on the instagram post or tweet me with your thoughts! I look forward to recording and sharing more episodes of The Motivated Classroom with you all in 2021!

Like many of you I have been going through a period of introspection and reflection on practices in my Spanish classroom and how I ensure I am always striving to have equity, social justice and respect at the heart of my teaching.

During this period I've been trying to focus on reading and listening to other voices. Using 'Spanish' names in the classroom has come up in a lot and I'd love to hear your thoughts and advice on my reflections.

Up until now I've always provided a list of Spanish names and nicknames to students at the start of the year. They are free to choose one if they wish but do not have to. I must admit that I have strongly encouraged them to go ahead and choose one though. In hindsight and upon reflection I feel this was wrong. The last thing I want is for a student to leave their own unique identity or culture at the door.

I've provided this list and allowed students to choose a Spanish name for themselves in the past as a lot of my doctorate research is on motivation and engagement. The three pillars of building intrinsically motivated, self-determined learners are:

- Competence

- Relatedness/Belonging

- Autonomy

The goal for students choosing their own unique Spanish name or nickname for our 'Españoland' class was always to build a sense of belonging and community to our class, whilst also providing them with the autonomy to choose whichever name they preferred, or what they felt they identified most with. After doing this for the past seven years, I'm quite convinced that this strategy does build a very special bond to our class. Students smile and beam when I greet them with this name, like we have our little secret society in our class. At parent meetings, they'll proudly tell parents.. "No Mum, I'm 'Juan' in Españoland". If we watch something where 'their' chosen name comes up, they get very proud and say things like "él también se llama Juan!". If I use their real name in class, they'll say "Señor, soy Juan aquí, no John". They feel like they are part of the Españoland family, like they have a special bond and belonging. It really helps to build relatedness and relationships. It's motivating.

In addition, I've had students use this opportunity to choose a new name as away to explore their sexual identity. I have two girls this year, age 12-13, who both chose Spanish male names. I double checked with them that this is what they wanted and each girl, individually, told me 'yes, I've always wanted a boys name' or 'I feel much more like a boy so I want a boys name'. For me, this was great. They were openly using boys names with their classmates in what felt like a way to express to their peers 'I think I identify with being a boy' or at least were eager to explore this openly. All of these things lead me to believe that allowing students to choose their own Spanish name for our class is something positive...

But...

Is this strategy disrespectful, offensive or harmful to native members of the Hispanic community? Is this practice unwittingly forcing students to denounce their own unique culture and name, and replace it with a new one? I must shamefully admit, I had not fully considered this until recently. At this point, it is important to understand the context of our classroom. I am a white, Irish, male teaching Spanish in Switzerland to students in an international school from all over the world. In a class of twenty, there would be typically around 15+ shared languages. I rarely, if ever, have 'heritage' speakers in my class. The demographics of our school are mainly northern Europeans or white people (around 75%), with the remaining 25% from all over the world. We have a small community of black and ethnic minority students, around 5-10% in total.

I have lived in Spain and have family there but I do not identify as Spanish. I identify as an Irish man who teaches Spanish and lives in Switzerland. So I realise I need to listen and learn from the Hispanic community on this. When I was reflecting on all this, I was trying to find a way for me, as an Irishman, to understand why my South American friends in particular, are so against students choosing their own 'Spanish' name. They've explained to me that it is mainly due to the underlying links to Spanish colonialism. So to understand this, I tried to imagine what it would be like for me.... If I walked into a classroom in, let's say, Turkey, and there was, let's say, a French person teaching English to a group of international students... and they had asked all their students to choose an Irish name from a list for their class, how would I feel? As an Irishman, I think I'd immediately think... "Why can't they just use their own names?".. but I would also think, "that is really cool that they are learning Irish names like Sineád, Siobhán, Aoife, Caoimhín, Gearóid... it's great they are learning some Irish culture through our names"... but... if they all had traditional 'English' names like John, Sarah, Tom, Elizabeth, George, I would probably be quite taken aback and also quite resistant. Why? Because as an Irishman I have a deep understanding of the oppression that was forced upon Irish people by the British occupying forces. An oppression that lasted 800 years and tried desperately to eradicate the Irish language and all Irish sounding names, but the language and those names survived. So an English teacher from France asking his international school class in Turkey to pick 'English' names would not sit well with me, even though that teacher never meant any offense or disrespect. Similar to my South American friends, I think it would unwittingly trigger links to colonialism for me personally even though all they were simply trying to do was build community in their classroom. I do not mean any offense by this, or to be political. I am merely trying to empathise and understand the issue from the perspective of my South American colleagues. For me, rightly or wrongly, the only way I can attempt to understand it is through my own cultural lens of Ireland's history.

And I guess with that I come to some kind of conclusion... we make decisions that we feel are for the good of our class but sometimes we are unaware of the cultural connotations, especially, I would argue, when we are teaching a language (and culture) that is not our own. I frequently feel inadequate, an imposter, a fake, for teaching Spanish when I am not a native speaker as but this makes me all the more passionate to try and get it right. To teach all parts of the culture and the history, the good, the bad and the ugly. The awful things the conquistadores did to the indigenous people, to the beauty and wonder of the present day Dia de Muertos tradition and celebration.

So where does that leave us on allowing students to choose a Spanish name for Españoland?

With all I've read and listened to, I feel I need to change this practice. I would love to know your thoughts on this. Especially, those who come from a Hispanic community or tradition. Do you allow students to pick a Spanish name they like or identify with? Or should we maybe only provide a list of cute Spanish nicknames? Or has this practice in all its forms had its day and it's time we just leave it completely? I think it has.

There is one thing I am definitely done with. If students do not want a Spanish nickname, even one that occurs naturally through the year, there will be no pressure whatsoever from me to have one. In fact, I am determined to embrace, uphold and celebrate their own name, heritage and culture. This is what I should have been doing all along.

Until recently, a lot of second language acquisition research has focussed on negative emotions and de-motivation. However, thanks to the work of researchers like Jean-Marc Dewaele and his colleagues, among many others, we are now learning a lot more about the importance of positive emotions and how to foster them. We can now say with some certainty that students crave unpredictability and novelty. When these are entrenched in classroom activities, students’ attention is ignited as emotions are further heightened. This research offers some further answers as to why students in language classrooms are so motivated by learning through storytelling. Almost every good story keeps us listening as we don't know what is going to happen next, this unpredictability keeps our positive emotions firing as we intently listen to find out what happens next.

The ‘unpredictable’ and ‘surprising’ elements are cited in the research as particularly important in encouraging emotional investment in the classroom and are also reported as highly motivating and crucial aspects of TPRS storytelling. Much of the current research advises teachers to plan activities that result in emotional arousal, as this will encourage deeper learner investment, which fits very closely with the nature of a co-created TPRS story. The strong emotional connection that TPRS ignites in learners was highlighted by many learners in both of my own research studies as a core reason why they find it so captivating and motivating.

These research findings can also be taken past stories though and right into our other lesson plans when we are not doing TPRS. If you keep students guessing about what activity is coming next, they will be more positively engaged. This goes for al subjects too, not just the language classroom.

But how do we keep it unpredictable all the time?

Well, realistically we can't. But we can have a wide bank of compelling, comprehensible input activities that we call upon at (seemingly) random times. This keep the students' ears perked up and listening to our input. They don't know what might be next so they need to follow along so as not to suddenly be like "eh what do we have to do?". The mini-whiteboard is one of my go-to favourites to quickly mix things up in the class. The key is for you to keep the flooding of comprehensible input going while the students do something a little active. There are so many ways to achieve it:

- Listen and draw; then compare and comment

- Write 5 words linked to X theme, then pass them round and add more. Teacher takes longest list and uses it for more comprehensible input

- Listen to a song and write particular things you hear (foods, emotions, adjectives etc)

- Bingo: Write 3 words related to X theme; then teacher talks about the theme while students listen. If I say any word on their board they are out.

- Groups of 2: write all the words you can remember from X song; then they stand and each group shares 1 word going round the room. When your board is empty or you can't think of any more your team is out. Teacher repeats and comments using comprehensible input.

- Give one get one: list of words related to X, go round room give a word, get a word. No looking at other boards though. You have to try to communicate clearly first. This is where they are giving comprehensible input to each other as it is just 1 word and the sentence "do you have X word"

And the list goes on and on. Whenever I see students eyes or heads begin to drop a little, or that familiar glazing over look we all try to avoid, I quickly say "whiteboards", and "everyone up" and then do an activity with them where they will have to move around. Some teachers call these "brain breaks" and do stretches or movement games. All of these help to motivate as long as we keep them unpredictable and there is comprehensible input from you as the teacher. Have you spotted that keeping the comprehensible input going is key to all this??

But aren't we always told that our students need classroom routines?

Yes they do but there's a catch: I still have loads of routines in my class but they are almost all to do with behaviour and managing the class. They are not necessarily routines to do with learning (although they can be linked). For example, a common routine is that the students enter class to Spanish music with subtitles being projected. Another routine is they need that week's password to enter class each day and they must tell me 1 word they learnt that lesson before being allowed to leave. I have a student 'control' the doorway and check everyone has said the password. I control the exit word. So yes, there are routines but even these behavioural routines allow for autonomy and unpredictability: they never know what song will be playing when they come in, the password changes every week etc. So it is a great thing to keep routines going for behaviour but when it comes to learning activities, try to mix it up frequently, throw curve balls and do a wide variety of activities to keep them with you. And of course, keep the comprehensible input going by telling them stories about your life (embellish as you see fit!), your pets, your hobbies, your failures and mistakes, your goals and dreams. As long as they are never fully sure what is coming next, you have them. And when you have them, they're listening intently and acquiring more language.

The 'MLIE' actually stands for ‘Multilingual Learning in International Education’ but this ECIS MLIE conference genuinely was a lesson in excellence across the board, from start to finish. I had heard wonderful things about this global coming together of language teachers, students and policy makers from my amazing colleague @polyglotteacher and others who attended the previous event in 2017 when Dr Stephen Krashen was one of the keynote speakers. So you can imagine my reaction when the wonderful Susan Stewart, ECIS Multilingualism Lead, invited me to speak at the main conference and present a full day on TPRS storytelling at the pre-conference! Humbled. Anxious. Nervous. But overall, pure joy to even be considered alongside many of my bookshelf at a conference of this stature

At the previous instalment of this conference, Dr Krashen apparently divided opinions as many language teachers believe that ‘output activities’ still hold an important place in the language classroom and we do not need to only focus on ‘input’. For me at least, Krashen’s work on Comprehensible Input (CI) makes a huge amount of sense and it was only when I received training on how to properly provide compelling CI to my students through stories and other activities, that I saw a leap in both the students’ motivation, engagement and achievement as well as my own. Nevertheless, I am also open to the varied and many differing opinions held by other language teachers on the subject of acquisition and that is what I loved so much about this conference. Attendees all came with an open mind to learn from each other, appreciating that there is always more research to engage with, more examples to build upon… that quite simply, there is always more to learn.

This was precisely true of the group of 25 teachers from right across the globe who got in early and signed up for my pre-conference 1 day workshop on Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) before it sold out. Many of these teachers have been in the game for a lot longer than I have and many are ‘getting great results’ with methods that we were all taught with as school children. But.. they came to the workshop with a passion and desire to improved their practice. A willingness to throw out something old that isn’t working and to jump in and try something totally new that may well, at first, seem outside our comfort zone. And even better still, since the workshop took place, three separate schools have asked me to work with their teachers on developing TPRS in their school!

But why bother with TPRS or CI approaches at all if we are ‘getting good results’? Because that is not enough. As teachers of language we are also teachers of people. We all want more than just a number on a results transcript. We want to create lifelong learners who are inspired from our classes to go and try their few phrases with the local shopkeeper. Inside us all, we want to teach more than just grammar and rules (even if we as language nerds do love this stuff). We want to teach culture, music, traditions, songs and we are all natural storytellers because we are language teachers and we love to talk. We want smiles and laughter in our classroom much more than we want the correct verb ending. In my opinion, that is what brought people to this conference.

But the conference was about so much more than teaching techniques and tools to inspire. It was about the power of multilingualism and how it holds the key to unity. We had truly moving and inspirational keynotes speeches from Amar Latif, the man behind ‘Travelling Blind’ and refugee turned scholarship student at UWC, Leila. We heard about the changing face of international education from the University of Bath’s, Mary Hayden, former Head of Education Department where I am currently doing my Doctor of Education studies. We had the timely reminder from the great Dr Jim Cummins alongside the equally wonderful Mindy McCracken and Lara Rikers about the pedagogical power of allowing students to share their own unique cultural identity. We had incredible practical sessions on how to engage learners from all backgrounds by the fantastic Beth Skelton and Tan Huynh. We also had the jaw-droppingly awesome presentation by middle school students at the International School of London about their University-level research project into bilingualism. Truly inspiring what children are capable of when given the means and parameters to succeed.

For me though, I left not only with my head buzzing full of ideas, but with the important take-home point that we must encourage our students to call upon, share and utilise their home languages and cultures in our classroom much more than we currently do. As a Spanish teacher in an international school where the language of instruction is English, I fall into the trap of establishing meaning by simply translating to English as “they all speak English” but the reality is that over 60% of my students do not actually speak English at home. The research is strong that the more linguistic ‘hooks’ they have to hang the new language onto, the better they will understand and the more they will acquire. This doesn’t mean that I reduce the amount of comprehensible input I give them, as they need lots and lots of CI through reading and listening to acquire language. Rather, the conference reminded me that if I don’t at least encourage contact with their home language in my classroom, then I am forcing them to leave a part of their identity, a part of their culture, a part of themselves, at the door. This is not right. All languages that students come to us with, should be embraced, celebrated and utilised as learning tools.

Trust me, put your professional development budget aside and book yourself on to the next ECIS MLIE 'Mega Lesson in Excellence' Conference. Total game-changer.

During the Agen Workshop this summer, I heard and learnt a lot about teaching with an ‘untargeted comprehensible input’ approach and have been trying it out during the first two weeks of school. When we teach with stories using TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) we usually have very specific structures in our head that are ‘targeted’ as the key learning goals for that story. For example, a beginner Spanish story might have había = there was, fue = he/she went and olvidó = he/she forgot, as the three structures we want to repeat many times so they are acquired naturally by the learners listening and partaking in the story.

Teaching in an ‘untargeted’ way essentially means we start up an activity or conversation with the learners and whatever language they need to communicate becomes the focus of the lesson… or at least that is the way I go about it! One such method is having the students invent and create a ‘character’ or ‘personality’ for your stories using an approach called ‘the invisibles’ or ‘one word images’. Based on what I observed Margarita Pérez doing during the Agen Workshop, I had the students sit in a circle with no desks and then give me any ‘invisible object’ that was in our class in front of us… they used English if they didn’t know the Spanish word and I translated. After they had all given their idea I had them pick which one they liked best and then we started to give that object (we had 'invisibles' such as a piece of glass, a marker and a basketball) personality traits and a history.

Margarita Pérez having students create an invisible character

I genuinely had no idea how this would go but I had 100% engagement from everyone as we built these characters as a team and students received constant repetitions of various structures at a level comprehensible to them. In one class, they really wanted to say “she used to play but not anymore” so we went with it and I briefly explained the differed between jugaba = used to play and jugó = played. This is all based around Krashen’s ‘natural approach’ and making the input so compelling that students get lost in the acquisition without thinking about it.

In reality even if it is ‘untargeted’ we immediately start to ‘target’ various structures once the students have identified them as a phrase they need to communicate. The important thing is to limit these to just a few key structures and then repeat and circle them (ask many varied questions while using the structure) as much as possible so students are getting the required repetitions for acquisition. I tried this out in a number of classes and I feel like it went very well although it is still very early days… so let’s see how much language was actually acquired when we go back to class tomorrow after field trips!