August 2, 2024

If you are a language teacher based in Europe you must get yourself to Agen, France next summer for the next instalment of this incredible week of meeting, laughing and sharing with like-minded passionate teachers. I am sure most of you have been to ‘professional development’ workshops before that left you far from… well, ‘developed’. This workshop is different. You walk away feeling professionally enriched, enthused, motivated, supported and connected.

When I first heard about the Agen TPRS workshop, I was excited to have the opportunity to meet and learn from amazing teachers from around the world but I was a little apprehensive that it was for an entire week in the middle of my long awaited summer holidays. I arranged to attend the conference from Monday to Friday morning, planning to leave at lunchtime. However, after just a few days I could see why people love this week so much. The workshops, the presentations, the activities but even more so, the social aspect… picnicking in one of Agen’s beautiful parks as the sun was going down, chatting about pedagogy and motivation with other like-minded souls. I was sold. I was all in. I quickly cancelled Biarritz and booked the Friday night in Agen too so I could attend every session right up to the final one on Saturday morning.

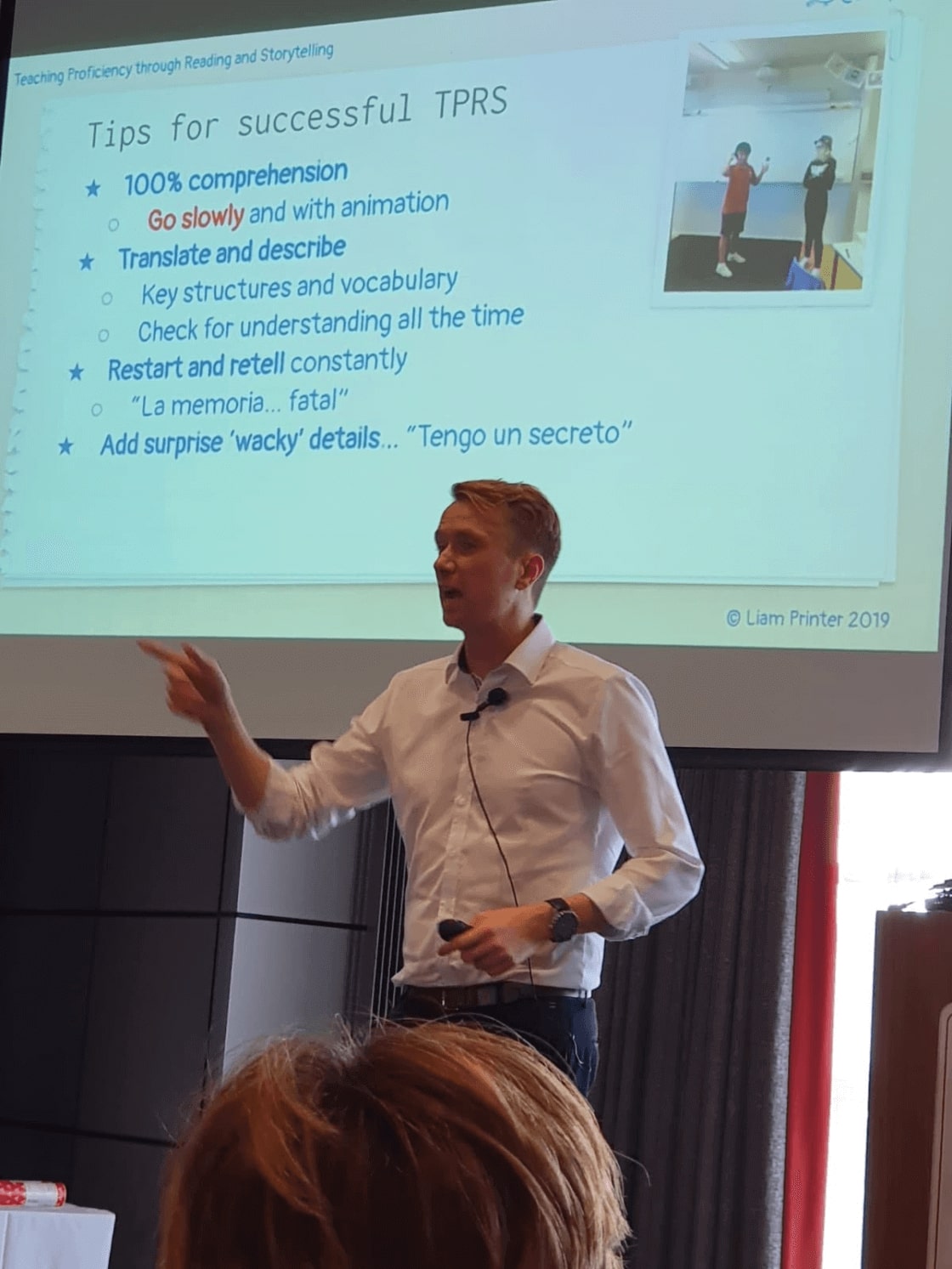

The workshop focuses on teaching strategies related to Dr. Stephen Krashen’s ‘Comprehensible Input’ (CI) theory and the method of ‘Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling’ (TPRS). The fundamental principle of CI teaching is to give students vast amount of ‘input’ (through listening intently and reading) at a level that is close to 100% understandable so they acquire language naturally rather than having to ‘learn’ it through drilling and practising. The results that CI teachers are achieving in a short amount of time are astounding… but the more important part, for me at least, is that CI students adore their language class; they find it fun, entertaining and are highly motivated to speak the language outside class and to continue learning it into the future.

This isn’t just anecdotal either… the research around TPRS and CI points to increased retention and numbers of students taking the language. As part of the Doctorate in Education that I am completing with the University of Bath, my research study with 12 high school students (full text here) found that TPRS was highly motivating to them and led them towards feeling intrinsically motivated – learning Spanish out of pure joy and interest rather than because of extrinsic rewards. Surely this has got to be our core goal as teachers. For our students to not only acquire language rapidly and achieve their potential, but to love our subject so much that they can’t wait to use their learning outside class and are eager to keep learning more about it long into the future.

Susan Gross kicked us off with a witty, engaging, keynote address about the history of CI and TPRS on Monday afternoon after an ‘official welcome’ to Agen at the Mairie. For those who have not been to the Agen Workshop before, the mornings are ‘language labs’ where you can be part of a real language class for the week or simply drop in and observe some exceptional teachers, hand picked from around the globe, working their magic. The afternoons are dedicated to workshops and presentations focusing on various strategies that aim to increase our use of CI in the classroom by sharing our practice with one another.

During the week, I had the pleasure of attending a Japanese class with Pablo Ramón, French with Sabrina Janczak, Spanish with Margarita Pérez Garcia, Mandarin with Diane Neubauer and Breton with Daniel Kline Longsdon Dubois. In my current school we have an open door policy where we encourage anyone to come along and observe but the reality of a busy school week often means that we don’t observe or have observers anywhere near as often as we would like. The week in Agen gave me that opportunity to just go, watch and take notes from truly expert teachers, masters of their craft, for 2.5 hours per day and then to chat with them over lunch, picking their brains for more tips and tricks I could steal for the benefit of my students. Each of them has inspired me to try new things in September and I now have concrete goals and examples to aspire to. A major take-away for me, from these observations, was that despite entirely different styles, with some teachers being very extrovert and animated, and others very calm and collected, TPRS was equally as successful in both these situations. TPRS can sometimes feel like you have to be quite a ‘big’ personality to do it well, but this is simply not the case. You must stay true to who you are as a person, as a personality and as a teacher but if you employ the skills and principles of CI and TPRS, both the achievement and the engagement in your class will take a dramatic upward turn.

In the afternoons, you have three choices to choose between. Although they are broken up into Track 1 (new to CI), Track 2 (developing with CI) and Track 3 (experienced with CI), in reality you end up jumping between the Tracks a little depending on your particular interests and what the presenters have planned. As I was presenting twice during the week I could not get to everyone but the ones I did see were all carefully planned, presented with enthusiasm and gave me a host of ideas to implement when I get back to school.

Scott Benedict showed us some clever ways to successfully carry out speaking assessments and then later in the week gave a plenary on classroom management with a CI focus. Laurie Clarcq gave us very practical, hands-on activities and skills aimed at increasing the amount of CI in our classrooms while Diane Neubauer demonstrated the power of ‘listen and draw’ both for comprehension checking and for maximizing input in the class and also led a plenary session on current research and issues in second language acquisition. On Wednesday, Robert Harrell explained how to use ‘Breakout’ (think Escape Rooms in the classroom with a box) to encourage ‘reading for meaning’ at the same time that Adriana Ramirez presented on her ingenious use of personalized photos in the class to encourage and develop oral fluency. I could only attend one so Adriana kindly gave me a mini 1 to 1 presentation on her ‘picture talk’ as I had heard such great things about it from others. At the end of the week, Adriana also went through what a whole week of TPRS and CI looks like for her.

The inimitable Jason Fritze explained how to take Total Physical Response (TPR) to a whole new level, backward planning it into our lessons to enable students to read more and then developed this further in his plenary on Saturday morning. Alice Ayel talked us through her use of ‘Story Listening’ and the results it has achieved, and then delivered an example for the whole group so we could see it in action. The final session on Thursday afternoon for me was Sabrina Janczak’s ‘Star of the Day’, where a student is the ‘star’ who is interviewed in front of the whole class allowing for lots of rich input and encouraging a real sense of community among the students. The last session on Friday was a big discussion on the use of the ‘Mafia’ game, facilitated by Diane Neubauer, with a focus on how it allows us to maximize the amount of CI we can get into a lesson while students are intently listening so they can follow along in the game.

It is clear why the Agen Workshop is so motivating, as it meets all three of the basic psychological needs required for intrinsic motivation as outlined in Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci 2000):

- Autonomy: You get to choose which sessions you want to attend in the afternoons and which teachers to observe in the mornings; it is also very inclusive so you feel like your ideas and contributions have merit and are accepted by the group.

- Relatedness: There is an immediate sense of community and togetherness at the workshop as we are all working towards a common goal of boosting motivation and allowing students to acquire language naturally through CI. In many cases, we are ‘lone wolves’ in our respective schools, maybe the only CI teacher in the department, but at this workshop everyone is so passionate about CI and has seen its results. It brings everyone together immediately. The social events (especially the 2.5 hour lunches!) and also foster a genuine feeling of belonging as we chat together about pedagogy and teaching over the incredible French cuisine.

- Competence: Even if you are new to CI, by attending the workshop you start to feel like you can really implement some of the principles in your classroom. The more sessions you attend and more times you practice the techniques, the more comfortable and competent you feel about being a CI practitioner.

Before you book anything else next summer, book onto the Agen workshop. Think ‘working holiday’ in Southwest France with lots of like-minded people, passionate about improving their practice and more importantly, improving their student’s outcomes. Put it in the Agen-da now! You can thank me later.

Wasn’t it Einstein who defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”? On Friday my twitter feed lit up with news that the UK government had “announced the creation of a national language centre and nine schools that will lead language hubs in a drive to improve the teaching of Spanish, French and German”… sounds great doesn’t it? And they are throwing £4.8 million at the initiative over the next four years, with the aim of “raising standards of teaching in languages”… all very positive so far, right? In addition, it seemed this was an evidence based proposal coming from “recommendations made in the Teaching Schools Council’s Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review led by headteacher and linguist Ian Bauckham.” I was genuinely feeling very optimistic and excited about this… until I clicked the link that is.

Let me be clear, I am not from the UK, I have never taught in the UK and I do not live in the UK. So why am I bothering to write this blog? Well, I work in an international school with many British teachers, parents and students. I have a large group of teacher friends who are British and my girlfriend is also British. I am also completing a Doctor of Education programme at the University of Bath in the UK and there is a strong likelihood I will teach in the UK at some stage in the future so their language education policies are important to me. From numerous conversations with Britons of all ages, it seems languages are taught, for the most part, in a very similar to way to how I was taught and how many teachers continue to teach.

In the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review that underpinned this big announcement, there is a distinct focus on continuing down the road of old school grammar and vocabulary teaching. Yet there is also references to students becoming demotivated and disinterested. Let’s just put this straight out there and say it clearly: these two concepts are closely linked. In my 11 years of teaching, I have chatted to hundreds of students and parents, and they say the same thing my classmates and I said 20 years ago when you ask them about their language class… it’s boring! It is just fill in the blanks, vocabulary lists, worksheets, grammar tables and stilted, forced “talk to your partner” conversations about ‘Pierre from Paris who likes baguettes’. Yes, there are some students who like learning this way but the vast majority are bored stiff and only keep going with the language as they perceive it as useful or their parents tell them it will be useful one day. The sad thing is that it does not have to be this way.

I was one of these textbook, grammar table and vocabulary list teachers too but then I discovered teaching with “Comprehensible Input” (CI). It is a well established theory of language acquisition, coined by Dr Stephen Krashen. Dr Krashen’s work does not feature in the appendix of the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review, and the word “comprehensible” is not present anywhere in the 27 page document. Yes, like everything in the world, it has its critics but those critics are certainly not my students, or the students of the thousands of CI teachers (and growing rapidly) around the world. This is not just some passing ‘fad’ or ‘method’. More and more teachers are converting to CI teaching as they see the incredible achievement and fluency it fosters but more importantly, their students now love their classes and their teachers love teaching them.

Some (not an exhaustive list) of the fundamental principles of CI are:

- Students require vast amounts of input (listening and reading) at a fully understandable level in order to acquire language; yes, we do modify and slow our speech to the level of the class so that it is almost 100% comprehensible by everyone at all times.

- The input is planned and taught in a way that is ‘compelling’ to students. They become so immersed in listening intently to what is happening that they acquire language without even knowing it.

- For this reason, we teach with stories (both ones invented by the class and other fables and tales). A key ingredient in the CI mix is ‘Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling’ (TPRS); where students and teachers co-create a fun story together (more on this below)

- Students’ personal interests and their lives are the centre of our input; we are always looking for ways to include things about them in what we say and what they read.

- We do not shelter grammar: teachers speak using natural conversation and do not only use, for example, present tense in the first year. We do not, however, go into long grammar explanations but maybe give short “pop up” explanations if required.

- We do shelter vocabulary: no more long, useless lists to memorize which are organized by chapter in a text-book. I see words in vocabulary lists of text-books aimed at Level 1 students that I (as their teacher) have never seen before or if I have, I certainly can not ever remember actually having to use it.

- Instead students get lots of repetitions (through reading and listening) of the most common and frequently used structures in a language for communication; for example, “there was, we went, I saw, he has” etc.

- No forced output: students are not forced to speak and write before they are ready, after lots and lots of comprehensible input. Patience is crucial. The output will come and you will see that the less you force them to speak to more they want to speak.

I can already see some language teachers who are unfamiliar with this shaking their heads and saying “that would never work”… but it does. While the research around TPRS is still limited, it is growing. Karen Lichtman’s overview of all the current TPRS research shows that students achieve very highly when compared to traditional methods. In fact, 87 of 88 of my students mentioned "stories" as one of three things that helped them learn most in their end of year feedback surveys last year.

More importantly though, for me at least, is that both students and teachers find it to be highly motivating. My own doctoral research with the University of Bath focusses on this ‘motivational pull’ of teaching and learning languages with TPRS and the data is overwhelming: Students love learning with TPRS. As Stephen Kaufman of LingQ pointed out so aptly in his tweet “Unfortunately too few language teachers recognize that the role of the teacher is not to teach the language, but to motivate the learner to learn the language.” We all need to remember this. If you focus on the motivation, the students will do the learning and acquiring themselves. TPRS gives you a tool that will motivate your learners and they will come to class in eager anticipation. As one student said in my research study about learning through stories:

TPRS is just one piece of the CI jigsaw. There are loads of other ways to get the vast amounts of comprehensible input, that students need, in to the class like Movietalk, one word images, picture talk, star of the week etc but the aforementioned principles stay the same.. and you’ve got to admit, it makes sense, right? We are all language learners, we have learnt and are fluent in at least one language already so we know we can do it. But how did we ‘acquire’ that language as we certainly didn’t learn it? Well, we listened and were read to for about two whole years before we ever felt ready to start to say some of those words. We certainly didn’t start off learning about adverbs, conjunctions and the irregular verbs in the passé compose before we could even speak and read the language. Or if our parents did start us off learning that way, I’m not sure how much love or motivation I’d have for the language (or for them!) today!

Yes, it is great that the UK Government recognize the importance of language learning and I applaud their consultation approach. However, I also implore the Minister for Education and the authors of the Modern Foreign Language Pedagogy Review to do their research. Go and read about CI and TPRS. Talk to teachers and students who are using it. Be ready for some enthusiastic and motivated responses. If we keep teaching languages in the same boring way we will have the same problems with uptake and retention for years to come. The frustrating thing is that we have the one subject that we can literally teach, talk and read about anything we want as long as it is the target language. We have the scope to be the most loved and interesting subject in the school. Any language teacher can do this by embracing ‘Comprehensible Input’ teaching approaches and working to make the input we give, “compelling” to our students’ ears and eyes.

So that I’m not accused of sitting on the fence… for me, motivation is the holy grail in education. It is the key to not only our students’ success but also to our own satisfaction as teachers. In this presentation at a recent all-staff meeting at The International School of Lausanne, I started by asking teachers to share ‘things that frustrate them’ about their students. Asking a question like this right at the end of a semester, with many tired faces in the audience, certainly didn’t take long to generate a rich variety of responses; not handing in work on time, arriving late and unprepared, not participating in class, constant low level chatter, using phones in class… I am sure most of us can relate to many of these issues that are common place in schools the world over. Next, I asked for the opposite; times when you felt you really loved your job, when everything was going well in the classroom. Thankfully, this also did not take long to produce a variance of answers; students all contributing, insightful questions, assignments that ‘wowed’ the teacher, students really enjoying their learning. I would argue that the bridge that fills the gap between these two phenomena is “motivation”.

When our students are motivated, they participate, they arrive on time, they hand in quality work, they ask great questions and produce thought-provoking, insightful, knowledgeable answers, they smile, they laugh, they want to improve, they want to learn.

What does this do to us as teachers? Quite simply, it makes us feel great. We feel good at our jobs, we feel like our kids are progressing, we feel like we chose the right career, we feel like we are making a difference, we feel motivated.

But how do we achieve motivated learners in our classes? Are there any ‘quick fixes’ for motivation we can apply straight away? Thank you to @MathsTweetcher for this question and the inspiration behind this blog.

The good news is that yes, there are things we can all do, with very little time and effort, to increase motivation right away amongst our learners. According to Ryan and Deci’s (2000) Self-Determination Theory (SDT), intrinsic motivation (which involves engaging in tasks out of pure joy and interest) is increased when we meet the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence. SDT, which originated in psychology, has already been extensively researched and tested across a variety of domains including medicine, coaching and education, and is widely considered and accepted as a robust method to augment motivation. Autonomy is related to choice, self-direction, and student ownership of learning; relatedness refers to a sense of belonging, support, inclusion and relationships while competence is concerned with students’ perceptions about their capacity to achieve success.

This 2006 study, for example, looked at the motivational pull of videogames and found that playing videogames clearly met the 3 needs of SDT and henceforth, why so many people are so motivated to keep playing them. Players have complete autonomy in where and what they do in any given game; there is a strong sense of relatedness as gamers have an immediate connection to a community where they can share their passion; and gamers feel a great element of competence while playing as they pass from one level to the next.

As part of my Doctorate in Education at the University of Bath, I also put SDT to the test in my own context, engaging in this qualitative research study with a group of Year 10 students (aged 15-16) about their experiences of learning languages through storytelling. Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) is a method of language teaching that, I found, consistently generated lots of positive responses on feedback forms and seemed to really engage the kids. In the study, according to the students themselves, TPRS visibly met the SDT needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence and this in turn meant it was a highly motivating approach to language learning. They reported believing they could “steer the learning” and “effect what would happen next” which led them to feel “more involved and more in control” of their learning (Autonomy). In addition, they felt the stories “helped them to understand everything better” and “really improved their speaking” (Competence). Finally, they reported that stories were “very extroverted” meaning “everybody will feel included” and “everybody gets to participate”, which made them “less scary” as “you don’t get judged” because “everyone was doing it as a group” (Relatedness).

Building self-determined, motivated learners does indeed take time but by applying SDT’s 3 needs to our lesson plans immediately, this can give us some ‘quick fixes’ to motivation as Jason asked about. Take a look at your upcoming lesson plans and ask yourself if you think the activities meet the needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness. Simply thinking about these needs as we plan can lead to more motivated behaviours:

Autonomy: Can I adapt the activity to allow students more choice or self-direction? You can still set the task but by allowing them different ways to show their learning and fulfil the objectives, you are heightening their level of autonomy and creativity, and you are on your way to a more motivated class.

Relatedness:Can I re-plan this so students have a greater sense of belonging and togetherness? Perhaps students can attempt a task in pairs rather than individually? Can students or (you as the teacher) share a personal anecdote connected to the lesson? Maybe there is an opportunity for you as their teacher to ‘get among them’ and do the task with them? All this improves relationships and leads towards more ‘relatedness’ in the class.

Competence:Is the activity going to help students feel like they can ‘do’ it? Is there a way to modify the activity so students can show off what they’ve just learned to each other? Another very simple way to augment students’ feelings of competence is just to recognize, highlight and share something good you see in the class, something that demonstrates understanding of the concepts. By explicitly highlighting successes and learning, students feel like they ‘are getting it’, they feel more competent.

Yes, building self-determined, highly motivated learners, can be a challenge but by making small adjustments to our lesson planning using SDT and creating an ‘ARC’ (Autonomy, Relatedness, Competence) in our classes we can at least help students to enjoy and engage in the lesson more, even if the content or subject matter is not of particular interest to them. If we want engaged, smiling, inquiring students who are achieving their potential and learning, its time we concentrated more on ‘motivating’ and less on ‘laminating’.

Please share your comments and whether you have any activities you feel already have students on an upwards ‘ARC’ towards motivation.

This was the general gist of a recent sit down I had with a school administrator when my grade distribution for the first semester looked very different from most other teachers. In my current school we use the International Baccalaureate (IB) grading levels, going from 7 as the highest grade to 1 at the lowest end. The administration noticed that my 'graph', as well as a few other teachers, looked quite different from 'the norm'. The vast majority of my 75-80 students were achieving a 6 or 7 with only a small number in the middle with a 3, 4 or 5 and no-one underneath that. To be fair to my school, the administration was not 'giving out' to me but rather they wanted to check in and understand why this was the case and find out whether my students were being adequately challenged.

I had never really looked or thought about my 'graphical distribution' of grades before. If the students achieve what is set out against the IB grading criteria, they then merit the high grades right?... but his question about 'are they all being adequately challenged' did make me stop and think. I went back and looked through some of the assessments I had set (presentations, story retells, writing out a story, reading comprehensions etc) and for each level I really do think these are challenging assignments. The "problem" (if that's what we can call it) is that the students are almost all really highly motivated, are engaged for 95-100% of the class time, only speak and listen to Spanish during every minute of every class and are all in a comprehensible input environment where we always seek 100% comprehension from each and every student before moving on.

I don't think it is 'me' in particular, but rather the comprehensible input methods I teach, which they have grown to love and cherish: storytelling, acting out parts of the book, movietalks, special person interviews etc. Is it so bad or so wrong that they are acquiring so much language so quickly that they are almost all acing every assessment they get? Is it not our goal to try and have highly motivated students as we know that will lead to achievement of their potential? Is it really my job to now go and set harder tests and evaluations so they don't all do so well, thus putting a lower number on some kids heads and demotivating them after all we have done to get this far together? I really hope not.

However, it does beg the question about maintaining sufficient challenge for each and every student. Of course, like in any class in the world, some students are faster processors than others, some need more repetitions of the structures and some don't. But I firmly believe in the Comprehensible Input mantra of 100% comprehension from all. Does this mean some students are bored? They never look bored. They never say they are bored in any feedback surveys. Quite the contrary in fact. So what is the problem if we are all learning, and learning so fast? What is the problem if they are all acquiring so much language that they ace all the assessments?

There is a cultural aspect to this too let's not forget. An 80% test score in an American school can mean a very different achievement level to an 80% score in a French or British school. The research is quite clear though, putting numbers on students heads, particularly low ones, demotivates much more than it motivates to improve. So why do we keep doing it? Why not just do away with grades altogether and just have comment only feedback for the first few years of secondary school (say up to age 15 or something). Is that really so radical?

As other language teachers around the world, I really would love to hear your comments on this. How do you maintain motivation whilst still having sufficient challenge for the high achievers? Do your comprehensible input methods also result in a 'skewed grade distribution' and if so... does that not just mean that what we are doing is actually working?

And most importantly, should we not be celebrating the 'skewed' graph rather than trying to reset it?

'Movietalk' is a popular method for language teachers to increase the amount of 'comprehensible input' in their classrooms through interesting little videos with lots of repetitions of new structures or vocabulary. Martina Bex gives a great overview of the method here. I too like to use it as a way to allow my students to hear multiple repetitions of language structures I want them to acquire, or ones I feel like they have not yet mastered.

My only issue with Movietalk was that until recently I felt like it was hard to 'circle' (asking the class and having them repeat the target structures) without it coming across as tedious or boring. For example, one of my favourite videos to use in December is this Justino 2015 advertisement for the 'Lotería de Navidad' in Spain. If I wanted students to acquire 'estaba trabajando', lets say, then I would pause the video a lot and keep asking questions about where and how he was working but half the time I felt like the students were looking at me like "Yes, we know he works in a factory, we have said this like 20 times and we have just seen it in the video... why do you keep asking us?"

Know that feeling anyone?

So now, what I try to do is make the video I am using much more interactive and more like a 'Movieaction' than a 'Movietalk'. I still do all the same steps as a normal Movietalk with lots of pauses and checks for understanding but I will also have a student become the character in the video and get him or her up in front of the class asking questions about what we have just seen in the video. This seems to hold their attention much better and it doesn't seem as 'repetitive' if I am asking this person about all the things we have just seen.

Remember, the key is to try to keep what we do 'compelling' wherever possible so I also use this character to bring in other characters from our recent story. I start with something like "pero clase, Justino tiene un secreto" and then it will turn out that Justino (our character in the video) "estaba trabajando" with 'Lady Gaga' or whoever else from our recent story. Not only does this little twist to the video seem to have them hanging on every word waiting for what happens next it also gives you the chance to do some 'formative assessment' and see if those structures you did 2 months ago are still there. Can they remember the old story? Can they use those structures we worked on 2 months ago? If they struggle then we go back over it all again. It really is amazing to see how linking to previous stories re-energizes the whole class again.

The final piece to the 'Moveaction' jigsaw is like so many of the other comprehensible input teaching approaches... slow down, take your time and get them out of their seats. I will have students use their whiteboards to write down new vocabulary from the video, then get up and swap them around or they will write 3 key parts of the video (using the target structures) with their partner, or draw a key scene from the video. The important part is putting the 'action' in 'Movieaction', having them get up, swap phrases, tell each other etc.

When you do these and you walk around and see just how many students have chosen to write or draw your new 'secret detail' with links back to your old story, it is remarkable. These random, silly, stupid, arbitrary little links and details are in fact, the keys to success and the ones they remember and want to talk about no matter how funny or interesting the actual video is.

I know, I know… as a ‘comprehensible input’ (CI) teacher, I shouldn’t ever really be teaching ‘verbs’ but bear with me. Like most other self-proclaimed CI teachers, I spend most of time focusing on giving students lots of understandable input through stories, personalized questioning, ‘special person’ interviews among lots of other strategies. However, after a few weeks doing this I often get a couple of questions and requests from students about the other forms of the verbs that we haven’t done yet. After hearing various verbs and language structures in context and using them in stories, a certain number of students will always want to see the whole verb written down so they can make connections and patterns to other structures they want to use. Once a few of these requests come in, I usually pick one entire verb that we have been using in the stories and ‘teach’ it through this activity.

Here’s how it would work. Let’s say we have been doing a story about food and restaurants using the verb ‘pedir’ to order. First, I will break students into teams and see if any team can write all versions of the verb ‘pedir’ in the past. They’ll usually get the ones from the story immediately and I might have to show them the other forms. Once we have all 6 subjects of the verb in the past tense they have 20 minutes to go and write a mini restaurant sketch using all 6 parts of the verb. This is where I love the atmosphere the stories create because they always come up with weird, wacky and wild sketches. It is a really great way for them to see that ‘pediste’ (you ordered) for example and ‘pidió’ (he/she ordered) are different and used for different people. I’ve found that many Anglophone students struggle with this as in English it is just ‘ordered’ for everyone.

The sketches really get them thinking in groups about how to include all parts of the verb and how to make it interesting. They then act it out in front of the class showing off the drama skills they have picked up in our stories.

If you want to make it even more fun, you can give a time limit of say 2 minutes for the acting of the sketch. Then have them all come back up and act it out again but each version they do, you cut the time limit in half. By the end they only have 15 seconds and will end up only saying the absolute key phrases in the sketch but which will undoubtedly contain ‘pedir’ in the past tense.

Zero worksheets, zero filling in the blanks, zero ‘rote learning’, zero confusion about which parts of verb apply to who through so many repetitions of a tough verb to learn, so many smiles, so much fun and so much acquisition.