August 2, 2024

Until recently, a lot of second language acquisition research has focussed on negative emotions and de-motivation. However, thanks to the work of researchers like Jean-Marc Dewaele and his colleagues, among many others, we are now learning a lot more about the importance of positive emotions and how to foster them. We can now say with some certainty that students crave unpredictability and novelty. When these are entrenched in classroom activities, students’ attention is ignited as emotions are further heightened. This research offers some further answers as to why students in language classrooms are so motivated by learning through storytelling. Almost every good story keeps us listening as we don't know what is going to happen next, this unpredictability keeps our positive emotions firing as we intently listen to find out what happens next.

The ‘unpredictable’ and ‘surprising’ elements are cited in the research as particularly important in encouraging emotional investment in the classroom and are also reported as highly motivating and crucial aspects of TPRS storytelling. Much of the current research advises teachers to plan activities that result in emotional arousal, as this will encourage deeper learner investment, which fits very closely with the nature of a co-created TPRS story. The strong emotional connection that TPRS ignites in learners was highlighted by many learners in both of my own research studies as a core reason why they find it so captivating and motivating.

These research findings can also be taken past stories though and right into our other lesson plans when we are not doing TPRS. If you keep students guessing about what activity is coming next, they will be more positively engaged. This goes for al subjects too, not just the language classroom.

But how do we keep it unpredictable all the time?

Well, realistically we can't. But we can have a wide bank of compelling, comprehensible input activities that we call upon at (seemingly) random times. This keep the students' ears perked up and listening to our input. They don't know what might be next so they need to follow along so as not to suddenly be like "eh what do we have to do?". The mini-whiteboard is one of my go-to favourites to quickly mix things up in the class. The key is for you to keep the flooding of comprehensible input going while the students do something a little active. There are so many ways to achieve it:

- Listen and draw; then compare and comment

- Write 5 words linked to X theme, then pass them round and add more. Teacher takes longest list and uses it for more comprehensible input

- Listen to a song and write particular things you hear (foods, emotions, adjectives etc)

- Bingo: Write 3 words related to X theme; then teacher talks about the theme while students listen. If I say any word on their board they are out.

- Groups of 2: write all the words you can remember from X song; then they stand and each group shares 1 word going round the room. When your board is empty or you can't think of any more your team is out. Teacher repeats and comments using comprehensible input.

- Give one get one: list of words related to X, go round room give a word, get a word. No looking at other boards though. You have to try to communicate clearly first. This is where they are giving comprehensible input to each other as it is just 1 word and the sentence "do you have X word"

And the list goes on and on. Whenever I see students eyes or heads begin to drop a little, or that familiar glazing over look we all try to avoid, I quickly say "whiteboards", and "everyone up" and then do an activity with them where they will have to move around. Some teachers call these "brain breaks" and do stretches or movement games. All of these help to motivate as long as we keep them unpredictable and there is comprehensible input from you as the teacher. Have you spotted that keeping the comprehensible input going is key to all this??

But aren't we always told that our students need classroom routines?

Yes they do but there's a catch: I still have loads of routines in my class but they are almost all to do with behaviour and managing the class. They are not necessarily routines to do with learning (although they can be linked). For example, a common routine is that the students enter class to Spanish music with subtitles being projected. Another routine is they need that week's password to enter class each day and they must tell me 1 word they learnt that lesson before being allowed to leave. I have a student 'control' the doorway and check everyone has said the password. I control the exit word. So yes, there are routines but even these behavioural routines allow for autonomy and unpredictability: they never know what song will be playing when they come in, the password changes every week etc. So it is a great thing to keep routines going for behaviour but when it comes to learning activities, try to mix it up frequently, throw curve balls and do a wide variety of activities to keep them with you. And of course, keep the comprehensible input going by telling them stories about your life (embellish as you see fit!), your pets, your hobbies, your failures and mistakes, your goals and dreams. As long as they are never fully sure what is coming next, you have them. And when you have them, they're listening intently and acquiring more language.

As a language acquisition teacher, we are tasked with helping our students write (as well as speak) accurately. We all know that feeling when we take up a piece of work and we see those errors that we feel like we have repeated a million times in class already! I am sure we also remember that feeling when we were a student: getting back a piece of work that we felt like we had worked so hard on, but it is covered in the teacher’s red pen. So how should we go about error correction and feedback then? How many errors do we correct? How do we ensure the feedback is meaningful and used to push the student’s learning forward, rather than so deflating that it pushes them back?

In short, the language acquisition research argues that most students can actually acquire only 3-4 new words or phrases per 1 hour lesson. Yes, that is all. By acquire I mean, the word or phrase is engrained in long term memory and recall. The same is true with error correction and feedback in writing. If you correct every tiny little mistake and missed accent, the student will only remember the ‘sea of red ink’ and it will do very little to develop their acquisition.

However, it is important not to forget the ‘outliers’; those students who, like us as their teachers, are linguists, grammatical nerds, who want to know every tiny error and why it is there. In my experience about 1 in every 20 students falls into this category. They are the ones who ‘ask’ about those sticky grammar points when you are mid-flow, sideways-laughing, at a funny part of a story. As you get to know them, you can and should correct all their errors but quietly explain to them that you are also a ‘grammar nerd’ and you knew they’d want to understand why the direct object pronoun is placed beside the indirect object pronoun. Then invite them to a ‘geek out’ at break time and go over it in detail. They will feel loved and fulfilled so now you can focus on the 99% who do not need or want that level of correction.

Ok so which errors should we correct?

In the pictures below is a student’s re-write of a story we were doing in class. This is a 13 year old student who has just started her second year of Spanish. The writing was done under exam conditions in class (ie. with no help from computers, dictionaries or teacher) in ten minutes. We had been co-creating the story together for about 5-6 lessons.

As you can see, I choose not to correct all the errors. Instead, I focus on the errors that were vital to our story, or that were part of our ‘target structures’. For example “compró” (he/she bought) was an integral part of the story so I am correcting that. The difference between “quiero” (I want) and “quieres” (you want) has been a target structure in previous stories and at this stage, it is something I want students to be able to differentiate. However, in the first paragraph, I did not correct spelling errors like “una persona” or “difícil”. Why? Because they were not the focus of the story. From the research on intrinsic motivation, we know that students need to “feel” competent, that they can do it. If we correct every tiny error, the basic psychological need of ‘competence’ (from Self-Determination Theory) is dampened and the student feels like they ‘just can’t get it right no matter how hard they try’. I know it is challenging to let your red pen glide over an error which is glaring to you as the teacher but pick your battles! Does this error confuse the message? Was it a key focus in your lessons recently? If not, forget it. It will come later with more reading.

So what about feedback?

I like to use Geoff Petty’s ‘medals and missions’. It translates easily into Spanish and students immediately understand it. Pick 2-3 medals and 1-2 missions. Yes, you need ‘more’ medals than missions no matter how difficult this seems, you have to find them. However, and here is the kicker: in the ‘medals’ it is vital that you focus on the ‘process of language acquisition’ rather than the ‘quality’ itself. Praise the student with things like “I can clearly see you are reading at home” or “you are obviously listening intently in class”. That way, the student sees that they will be praised for going about the process in the correct way rather than just getting the answer right by whatever means. I only started doing this in the last year but I have seen huge differences once I reframed my feedback on the process and not product.

For the missions, I will usually give them a goal to improve the language like ‘use more description’ or ‘include connecting words to give your story more fluency’ rather than on the language itself. Sometimes, 1-2 short bullet points on a particular area of language is a good idea though. The students also use this ‘medals and missions’ way of giving feedback when doing peer assessment together in later tasks.

A further point that has really improved the way I give feedback is that I always try to read through the entire piece once before putting a single red mark on it. Yes, this is soooo difficult to do, it's like the red pen has a little red mind of its own at times! But if the piece is not too long, I try hard to do this. Then I ask myself: Ok, did I understand most of that? Were there lots of details from the story? Did it flow together? Has the student been listening to understand? It really focusses my mind on what is important and then allows me to pick out just 4-5 errors to concentrate on.

What happens next with the feedback?

For homework, students must write out their corrections. No ifs no buts. They write them always in the same place in their notebook so that all their corrections are together as they go through the year. We do this in a specific way:

- The student writes out the correct version of the sentence

- Next they use a different colour to underline or circle where the error used to be.

At the end they have a list of 4-5 sentences for each piece of written work that has a circle on the correct version, where they used to make mistakes. I always tell them this is the page to study or look over before any assessment. It is like having a teacher on your shoulder saying “psst.. remember, its quieres to say ‘you want’”. It means each student has a page of corrections that is specific and unique to them. I also encourage them to look over these corrections before they start their next written assignment.

Let’s be honest, grading and marking is not why we got into this job. It’s never going to be ‘fun’ but at least with this method, it is time efficient and focussed on improvement. Most importantly, it maintains student motivation. It prevents them from feeling like a failure as they will never again receive a page of red pen that deflates and destroys all their hard work trying to get it right. Have a go and let me know what you think! Or if you have a better or more effective way of grading then please share… I’m all ears!

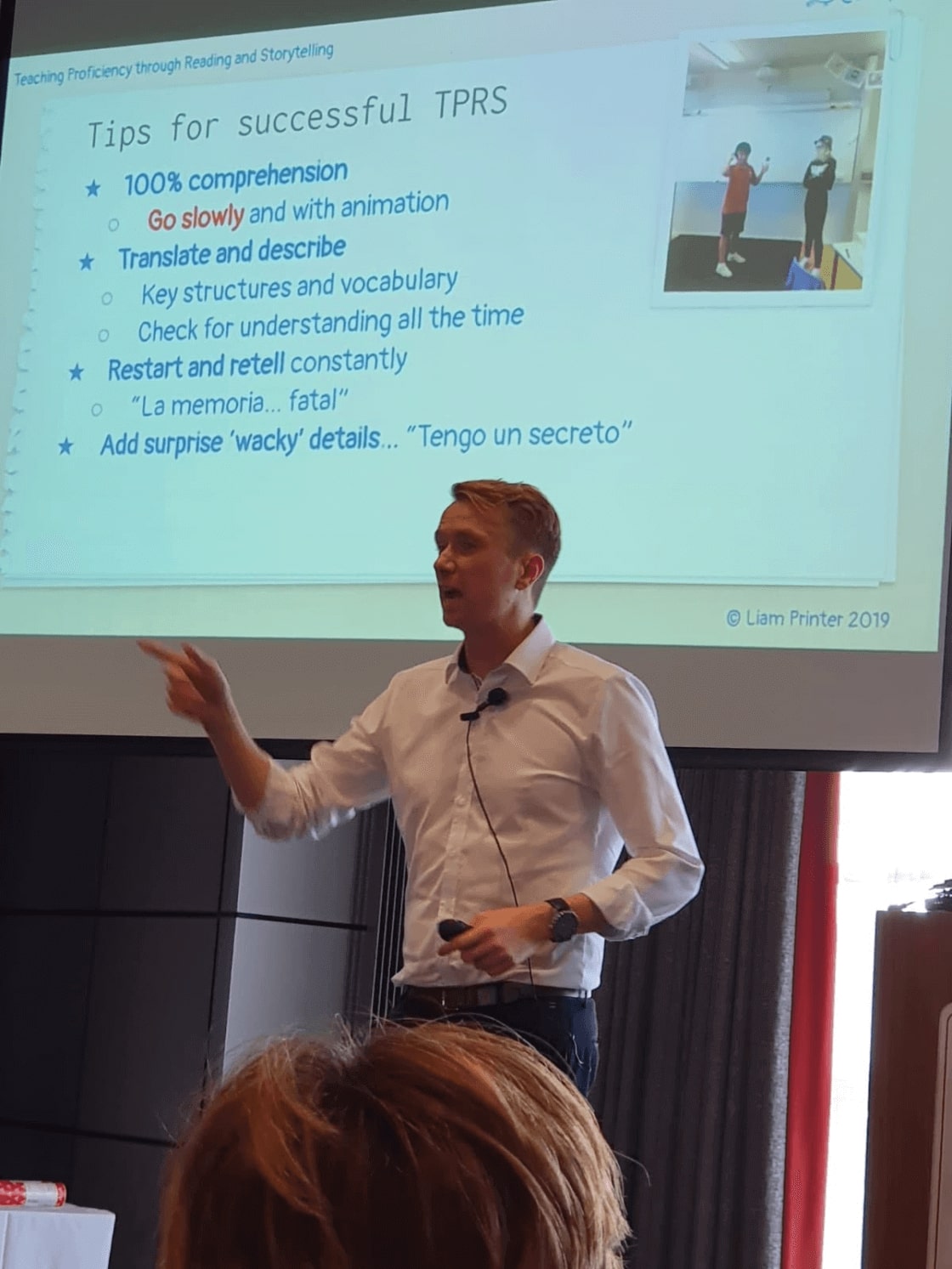

The 'MLIE' actually stands for ‘Multilingual Learning in International Education’ but this ECIS MLIE conference genuinely was a lesson in excellence across the board, from start to finish. I had heard wonderful things about this global coming together of language teachers, students and policy makers from my amazing colleague @polyglotteacher and others who attended the previous event in 2017 when Dr Stephen Krashen was one of the keynote speakers. So you can imagine my reaction when the wonderful Susan Stewart, ECIS Multilingualism Lead, invited me to speak at the main conference and present a full day on TPRS storytelling at the pre-conference! Humbled. Anxious. Nervous. But overall, pure joy to even be considered alongside many of my bookshelf at a conference of this stature

At the previous instalment of this conference, Dr Krashen apparently divided opinions as many language teachers believe that ‘output activities’ still hold an important place in the language classroom and we do not need to only focus on ‘input’. For me at least, Krashen’s work on Comprehensible Input (CI) makes a huge amount of sense and it was only when I received training on how to properly provide compelling CI to my students through stories and other activities, that I saw a leap in both the students’ motivation, engagement and achievement as well as my own. Nevertheless, I am also open to the varied and many differing opinions held by other language teachers on the subject of acquisition and that is what I loved so much about this conference. Attendees all came with an open mind to learn from each other, appreciating that there is always more research to engage with, more examples to build upon… that quite simply, there is always more to learn.

This was precisely true of the group of 25 teachers from right across the globe who got in early and signed up for my pre-conference 1 day workshop on Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) before it sold out. Many of these teachers have been in the game for a lot longer than I have and many are ‘getting great results’ with methods that we were all taught with as school children. But.. they came to the workshop with a passion and desire to improved their practice. A willingness to throw out something old that isn’t working and to jump in and try something totally new that may well, at first, seem outside our comfort zone. And even better still, since the workshop took place, three separate schools have asked me to work with their teachers on developing TPRS in their school!

But why bother with TPRS or CI approaches at all if we are ‘getting good results’? Because that is not enough. As teachers of language we are also teachers of people. We all want more than just a number on a results transcript. We want to create lifelong learners who are inspired from our classes to go and try their few phrases with the local shopkeeper. Inside us all, we want to teach more than just grammar and rules (even if we as language nerds do love this stuff). We want to teach culture, music, traditions, songs and we are all natural storytellers because we are language teachers and we love to talk. We want smiles and laughter in our classroom much more than we want the correct verb ending. In my opinion, that is what brought people to this conference.

But the conference was about so much more than teaching techniques and tools to inspire. It was about the power of multilingualism and how it holds the key to unity. We had truly moving and inspirational keynotes speeches from Amar Latif, the man behind ‘Travelling Blind’ and refugee turned scholarship student at UWC, Leila. We heard about the changing face of international education from the University of Bath’s, Mary Hayden, former Head of Education Department where I am currently doing my Doctor of Education studies. We had the timely reminder from the great Dr Jim Cummins alongside the equally wonderful Mindy McCracken and Lara Rikers about the pedagogical power of allowing students to share their own unique cultural identity. We had incredible practical sessions on how to engage learners from all backgrounds by the fantastic Beth Skelton and Tan Huynh. We also had the jaw-droppingly awesome presentation by middle school students at the International School of London about their University-level research project into bilingualism. Truly inspiring what children are capable of when given the means and parameters to succeed.

For me though, I left not only with my head buzzing full of ideas, but with the important take-home point that we must encourage our students to call upon, share and utilise their home languages and cultures in our classroom much more than we currently do. As a Spanish teacher in an international school where the language of instruction is English, I fall into the trap of establishing meaning by simply translating to English as “they all speak English” but the reality is that over 60% of my students do not actually speak English at home. The research is strong that the more linguistic ‘hooks’ they have to hang the new language onto, the better they will understand and the more they will acquire. This doesn’t mean that I reduce the amount of comprehensible input I give them, as they need lots and lots of CI through reading and listening to acquire language. Rather, the conference reminded me that if I don’t at least encourage contact with their home language in my classroom, then I am forcing them to leave a part of their identity, a part of their culture, a part of themselves, at the door. This is not right. All languages that students come to us with, should be embraced, celebrated and utilised as learning tools.

Trust me, put your professional development budget aside and book yourself on to the next ECIS MLIE 'Mega Lesson in Excellence' Conference. Total game-changer.

As a teacher, how do you measure ‘success’ in your classroom? Progress? Engagement? Learning? Unfortunately, the standard way to judge or quantify how successful you, your methods or your students are, is through ‘achievement outcomes’ or, more simply, ‘results’. Obviously, it is important that our students are learning, but I fear that the reason we have increasing numbers of students in the UK dropping languages is because we have slipped into a Machiavellian way of looking at language acquisition (and many other subjects) - as long as they are getting the results, then the methods don’t matter. The ‘ends justify the means’ per se.

Drill. Practise. Worksheet. Repeat.

The results will come and everyone is happy, right? The results often do come, at least for those willing to do the tedious practice and conjugation drills, but not everyone is happy. Perhaps the parents are happy when they see the ‘A’ on the results transcript, perhaps even the teacher is happy seeing those wonderful phrases we practised so many times reappear on the exam script, but no, not everyone is happy. The vast majority of students do not like rote learning, drills and practice. The research tells us students are ditching languages because, quite simply, they find it boring. In my own research, 11 years of collecting feedback forms at various stages in the year from students of all ages, backgrounds and contexts, I’m still at under 1% of responses listing grammar worksheets or practice drills as activities they felt helped their learning. They can serve a purpose when used very sparingly. However, in reality, far too many of us fall back on grammar exercises as our ‘go to – keep them quietly working’ activity when our students creativity and passion is dying a slow and painful death by powerpoint boredom.

The problem with focusing on achievement and results is that even when we appear to be ‘successful’, we still have far too many students (and parents) talking about hating French or ‘not being able to speak any Spanish’ even though they studied it for five years. Our subject is ‘language acquisition’ but what most students actually get is a linguistics class on the mechanics of language and grammar, sprinkled with some role-play and practice drills in case someone in the future should ask them any of the very precise questions in our textbooks. I remember going to Germany when I was 15 and had been learning German for three years… and to my shock and horror, even though I knew my lines, I had practised and drilled those role plays, the pesky Germans did not know theirs! Not one person asked me how to get to the post office or to list off all the items in my bedroom.

There seems to be a growing debate between language teachers and researchers about whether we should focus on ‘fluency’ versus ‘accuracy’ or on ‘meaning’ versus ‘form’. Personally, I am in the ‘meaning and fluency’ camp, with a strong belief that ‘accuracy and form’ come later. I am not saying we just ignore errors or never mention the G word (grammar), rather that we don’t make these the number one priority. The focus needs to move away from 'achievement outcomes' and towards 'engagement incomes'. Personally, and I have plenty of first-hand evidence to go along with the research on this, I think we need to ask ourselves the question:

Why teach with a focus on accuracy, form, grammar drills and practice when you get pretty much the same 'results', but with a huge increase in motivation, with a Comprehensible Input (CI) based approach?

I used to be a 'traditional' grammar, drill and practice language teacher for years. A pretty good one too. I was getting great 'results'. Most students liked my classes and were learning a lot. The 'academic' kids were excelling but others were simply not that interested no matter how hard I tried. I resigned myself to admitting "they just don't really like languages". Wrong. They just didn't find studying the mechanics of language as interesting as I did, like most other teenagers.

The switch to ‘Comprehensible Input’ teaching means I now reach all students. Even those who are not that 'into' languages, they still like Spanish and even after the timetable has forced them to drop it to pursue their love of Physics or Economics, they still come to me and speak Spanish, they still say they loved the class. This is what has changed. Grammar and drilling does 'work' for many kids, in terms of it helps them do very well on exams. But CI based classrooms grow a genuine love and interest for the language and the class and... here is the key, they also do really well on the exams.

My research focuses on the motivational side of language teaching and learning, and I do wonder why we continue to argue over which methods 'work' the best when we can't see the wood for the trees. We know that both 'methods' can deliver results but only one method is perceived as highly motivating and fun by almost ALL the students and not just some. The one that 'works' the best is not the one with fewer grammatical errors or longer error free iterations or even the one with greater fluency or accuracy. It is the one that keeps students coming back for more, the one that makes students want to go and look up a Spanish song at night, the one that makes them want to try that Spanish phrase with their Colombian piano teacher. When we focus on that part... the motivation part, the accuracy will follow, as you have peaked a desire in that student to go and find out for themselves why it is -o and not -a at the end of that word (if they really want to know!). If both methods get us the same results but one motivates much more than the other, one creates more smiles and laughs from both the teacher and the students, why are we even arguing about this?

I'm not making this up either… the limited research around the motivational pull of CI and TPRS storytelling teaching is very strong. The huge volumes of data we have relating to retention and engagement in traditional grammar, drills and practice classroom is also very strong, but strong in the other direction. Students are not motivated by it. Students end up dropping the language and becoming those adults who say "I did German for five years but I was so bad at it, I can't remember a word".

Those “I’m so bad at languages” comments that we hear from other adults when we mention our job, those comments are on us. It is not the students’ fault that they are not as enthused by nerdy grammar explanations that most of us, as language teachers and linguists, love. We have control over how we teach in our own classrooms, we can stop the rot and change the way languages are taught in schools.

First step: throw out the stack of grammar worksheets, forget all the drills and practice and just talk to the students. Tell them about yourself, your weekend, your fears and passions, tell them stories and ask them questions, real questions about their dreams and desires, do it all in a comprehensible manner focusing on the meaning and not the grammar, and you are on your way to a new vision of ‘real success’. One where you spend less time laminating, and more time motivating.

‘Success’ is measured not by how many points a student scores on a test, or by how many grammatical errors there are. ‘Success’ is measured in smiles. This is real success.

During the Agen Workshop this summer, I heard and learnt a lot about teaching with an ‘untargeted comprehensible input’ approach and have been trying it out during the first two weeks of school. When we teach with stories using TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) we usually have very specific structures in our head that are ‘targeted’ as the key learning goals for that story. For example, a beginner Spanish story might have había = there was, fue = he/she went and olvidó = he/she forgot, as the three structures we want to repeat many times so they are acquired naturally by the learners listening and partaking in the story.

Teaching in an ‘untargeted’ way essentially means we start up an activity or conversation with the learners and whatever language they need to communicate becomes the focus of the lesson… or at least that is the way I go about it! One such method is having the students invent and create a ‘character’ or ‘personality’ for your stories using an approach called ‘the invisibles’ or ‘one word images’. Based on what I observed Margarita Pérez doing during the Agen Workshop, I had the students sit in a circle with no desks and then give me any ‘invisible object’ that was in our class in front of us… they used English if they didn’t know the Spanish word and I translated. After they had all given their idea I had them pick which one they liked best and then we started to give that object (we had 'invisibles' such as a piece of glass, a marker and a basketball) personality traits and a history.

Margarita Pérez having students create an invisible character

I genuinely had no idea how this would go but I had 100% engagement from everyone as we built these characters as a team and students received constant repetitions of various structures at a level comprehensible to them. In one class, they really wanted to say “she used to play but not anymore” so we went with it and I briefly explained the differed between jugaba = used to play and jugó = played. This is all based around Krashen’s ‘natural approach’ and making the input so compelling that students get lost in the acquisition without thinking about it.

In reality even if it is ‘untargeted’ we immediately start to ‘target’ various structures once the students have identified them as a phrase they need to communicate. The important thing is to limit these to just a few key structures and then repeat and circle them (ask many varied questions while using the structure) as much as possible so students are getting the required repetitions for acquisition. I tried this out in a number of classes and I feel like it went very well although it is still very early days… so let’s see how much language was actually acquired when we go back to class tomorrow after field trips!

Classroom management is a recurring theme for most teachers. In the ‘comprehensible input’ classroom it takes on even greater significance as you are looking for intent listening, total engagement and 100% understanding from your learners. You plan compelling, interesting stories and activities, and this breathes life and even more energy into your teenage students. It can sometimes result in a fear of things getting out of control or too noisy which can in turn impact their acquisition. The ‘Class Constitution’ is a way to get immediate buy-in from your students on Day 1. By co-creating it together as a team you are building strong and meaningful relationships through mutual respect from the very first time you meet them.

The three core tenets of quality classroom management are: Clear expectations, Consistent routines and Strong relationships. The ‘Class Constitution’ hits all of these. It usually takes a full double period (for me that is 80 minutes) to do it properly. Dedicating a full class to this may seem like a lot but it is the best time investment you will spend all year and will save you hours and hours in the long run whilst also keeping you as that happy, enthusiastic and motivated teacher you want to be all year.

Step-by-step guide to your ‘Class Constitution’:

As students arrive on the first day, greet them at the door with care and respect, looking them in the eye. As they take their seats I tell them they are all no longer in school but in the ‘Embajada de Españoland’ (Embassy of Españoland). I bring them to the door and show them my 'border' (black tape on the ground and something we use a lot later on when talking about migration) and ask them to explain what they know about ‘borders’ and ‘embassies’ to me. For my total beginner students I tell them that normally in Españoland we only speak Spanish but just for today we will be doing everything in English. Yes, I know this is valuable time when they could be getting more input but in my experience, showing the students that this is important enough for a full double lesson sets us up for the year and allows me to have much more time giving them Comprehensible Input throughout the year as they are totally bought-into the process. With all other year groups/levels we do it in Spanish but I allow responses and group talk in English that I will translate for them.

Step 1: What is a ‘safe’ learning environment?

In small groups of three or four, students firstly have some quiet thinking time and then they chat about what a 'safe classroom' means to them. On large sheets of paper, they start jotting down ideas. You can do this in whatever way works for you but I usually have one big A3 piece of paper on each table, for every group, and it is divided into three sections. Each group writes their ideas in one section of their paper with the heading “safe”.

Step 2: Teacher led discussion

After 5 minutes (or less if you wish), I ask each group for some ideas or key words they wrote down. I jot these on the board, making sure to recognize any great words or concepts that come out. Obviously though, you, as the teacher, are a skilled practitioner and professional, so you keep probing for answers until they come up with what you really want to hear. Students will quickly realise that while silly or immature words are listened to but not accepted, the teacher gets very enthusiastic and excited about concepts like ‘respect, listening, we love mistakes’ etc.

Step 3: What is a 'fun' learning environment?

The above two steps are now copied in the same way but changing the focus to ‘fun’. I usually have each group move to a different table so they can see the words and answers that other groups wrote down. They can add some words if they wish. In the discussion part for this question you will see the enormous impact of the tone you set and the way you looked in their eyes and smiled when they gave you a great word in the first discussion. You will start getting really great stuff here right from the outset. Again, use your skills to facilitate a discussion until those key concepts start to surface.

Step 4: What does it mean to be 'linguist'?

The final section of their paper is about being a linguist. I introduced this last September and it worked wonders as a classroom management piece throughout the year. They follow the same procedure as before but you may need to explain what a ‘linguist’ is. I tell them that by being citizens of Españoland they are all now part of a very elite and special group, they are no longer mere students or learners but linguists. Just watch their faces light up as you call them ‘linguists’. When we get to the group discussion part, I explain that we as linguists, are different, we do not act like everyone else. What do we do that is different? After some probing, they will come out with things like “we respect other cultures, we listen to other languages, we read and inquire into cultural differences, we love speaking languages, we love listening to others talk in a different language” etc. This simple element of naming them for the whole year as linguists has a profound impact on behaviour, attitude and confidence.

Step 5: Pulling it all together

Once we have all our key ideas on the board under our three headings, I ask them what they notice. Someone will point out the word ‘respect’ has magically appeared in all three areas so this must be the centre and core of our constitution. We then circle and highlight other ‘big ideas’ or key concepts together. Finally, I ask them if it would be ok if I could represent them and pool all of this together into our very own constitution. I also ask them, “if we have an embassy based on these ideas do you think it will be a good year in Españoland?”, they inevitably will answer yes. I also explicitly point out and say that they did not walk in here and get handed a list of ‘my’ rules of the class. Instead, they wrote their own constitution, they came up with the key values and concepts of being a citizen of Españoland themselves.

Step 6: The next class

I start the next class by showing them their constitution… it is no surprise that all my classes have a constitution that is almost identical. I ask them if I have represented their ideas adequately and if they are happy that this be our ‘guiding document and principles’ for life in Españoland. There is also great cross-curricular learning here with Humanities; I often have the younger students speak to their humanities teacher about our constitution and allow them to show off that they know what it is and why it is important to countries and citizens to have one.

Throughout the year:

The constitution remains on our ‘embassy’ wall for the year. If there are any lapses in behavior or standards that we all expect from each other, I simply bring the student(s) in question to the constitution and point to the requisite section and smile. This usually does the trick but sometimes I might have to remind the entire class of our underlying constitutional values that they themselves designed and wrote. These lapses in standards are actually incredibly rare. In general, co-creating the shared ideals together results in a respectful classroom where everyone feels safe, where we have fun, where we act like the linguists we are and where we thrive upon our favourite mistakes as unique learning opportunities. I always remind students that “as linguists, we are special, we are unique, we listen intently to understand and therefore learn”. Simply changing the discourse and calling them linguists possesses some magical power to keep everyone engaged, enthused and eager to represent themselves as the linguist they are.

Planning to motivate not to laminate:

As my regular blog followers will already know, the thesis for my Doctor of Education studies is focused on strategies that motivate both the teacher and student in the language classroom. Specifically, I am looking at Ryan and Deci’s (2000) Self-Determination Theory relating to intrinsic motivation. It posits that when activities meet the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence, this results in intrinsic motivation; where we engage in something out of pure joy and interest rather than external forces acting upon us. This forms the backbone of all my classroom planning as, in my opinion, motivated students who like the class and want to be there, who want to listen and learn, make for great language learners. The ‘Class Constitution’ meets all of the three psychological needs of Self-Determination Theory:

- Autonomy: Students are co-creating this constitution themselves with the teacher; they have control, choice and ownership over what to suggest and what is ultimately included.

- Relatedness: Through building the ‘Class Constitution’ together in groups and then with me as the teacher, they are fostering strong bonds and relationships both to each other, to the teacher and to 'Españoland' itself.

- Competence: When the teacher acknowledges the students' ideas and then accepts their concepts as important enough to go into the constitution, the students feel ‘able’ for what is being asked, they feel competent.