August 2, 2024

My Year 9 class are now 4 weeks from the end of our second year together. The students are aged 12-13 and have had approximately 2 hours Spanish per week, minus all the school holidays of course. In those two years we have read 6 class novels and they've each read 10-20 other graded readers during their free voluntary reading time at the beginning of class. Since around 4 months into year 8 (their first year of Spanish), we have started almost every class with 5-10 minutes of silent reading. We don't have a textbook

In the two years, we've never 'done' or 'practised' a verb table. We have looked at one, after a student asked about the endings. We've maybe done two worksheets total across the two years that had a focus on accuracy. They have had plenty of pop-up grammar explanations about the differences between "comió" and "ha comido" for example. We don't do lists of vocabulary or regular high-stakes testing.

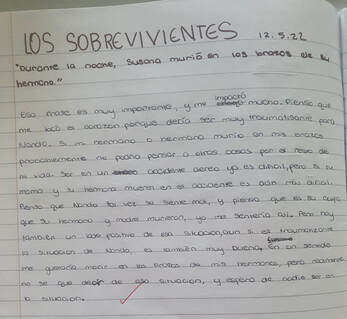

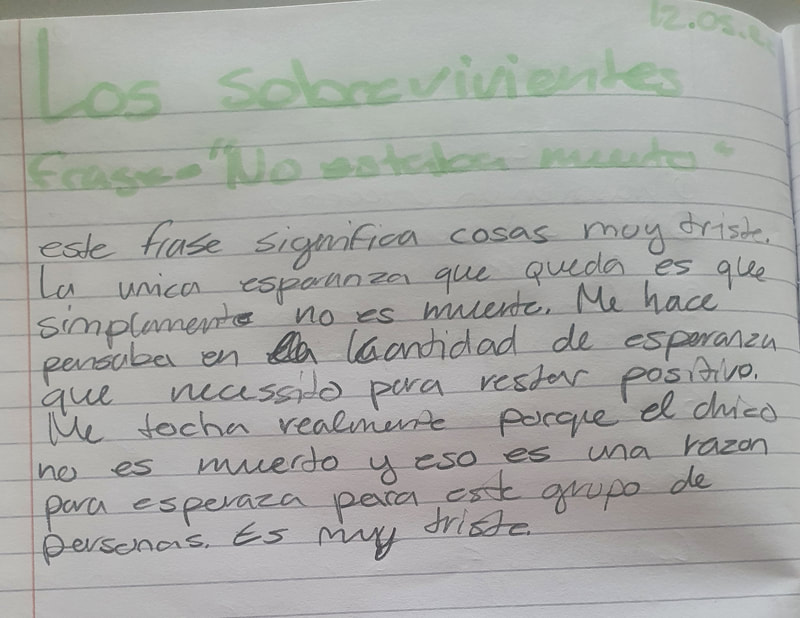

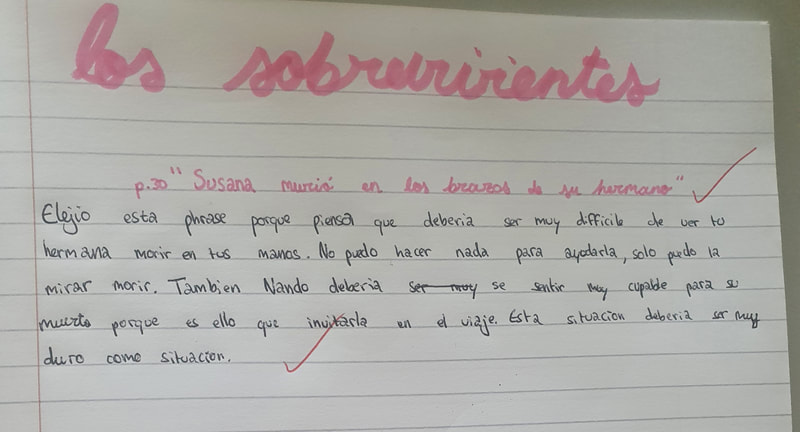

We have never done anything about the conditional tense; I've never (explicitly) taught them 'debería, sería' etc... but they are using it in their writing. Below are some of their most recent entries in their "Diario de Lectura". These entries are mostly done in class, with no dictionary or computer. Just free writing.

Diario de Lectura entries are done regularly based on phrases they connect with from books we are reading. I never correct any mistakes in their 'diario de lectura'. I do correct 2-3 critical errors when they are doing a formative writing piece before a summative assessment, but this is separate. In the diario de lectura, they know they can write without fear of being wrong. They know it is a conversation in writing between me and them.

And the clincher... hand on heart, these students allspeak more fluently and arguably with more accuracy than they write. I'll share recordings of our final round table discussions at the end of the school year.

Flooding students with compelling, interesting, and most importantly, comprehensible inputs that centre on narratives and stories from our lives, our identities, our passions, our fears and our cultures... works. It allows children to acquire language naturally; to learn about each other, about me and about the world.

Reading... lots of reading, works. The books allow us to regularly discuss big themes, important topics and social justice issues... and, it results in so much fantastic, impressive and fluent output.. both in writing and in speaking. Remember Grant Boulanger's mantra "The less you force them to speak, the more they want to speak".

In Year 3 next year we will start to look more closely at grammatical accuracy, at writing and speaking for different audiences, in different tones. But not before. Remember, they need to build the system first; before they can start to look more deeply at the components of that system.

Trust the process, trust the research, trust your students. Acquisition doesn't happen overnight but keep giving the rich, comprehensible inputs and it will happen. Leer es poder!

Many of the wonderful listeners of The #MotivatedClassroom podcast have been getting in touch to ask for examples of what students writing output looks like given that I focus primarily on lots of compelling, comprehensible inputs with little or no formal grammar tests or tasks, worksheets or vocab lists, particularly in first two years.

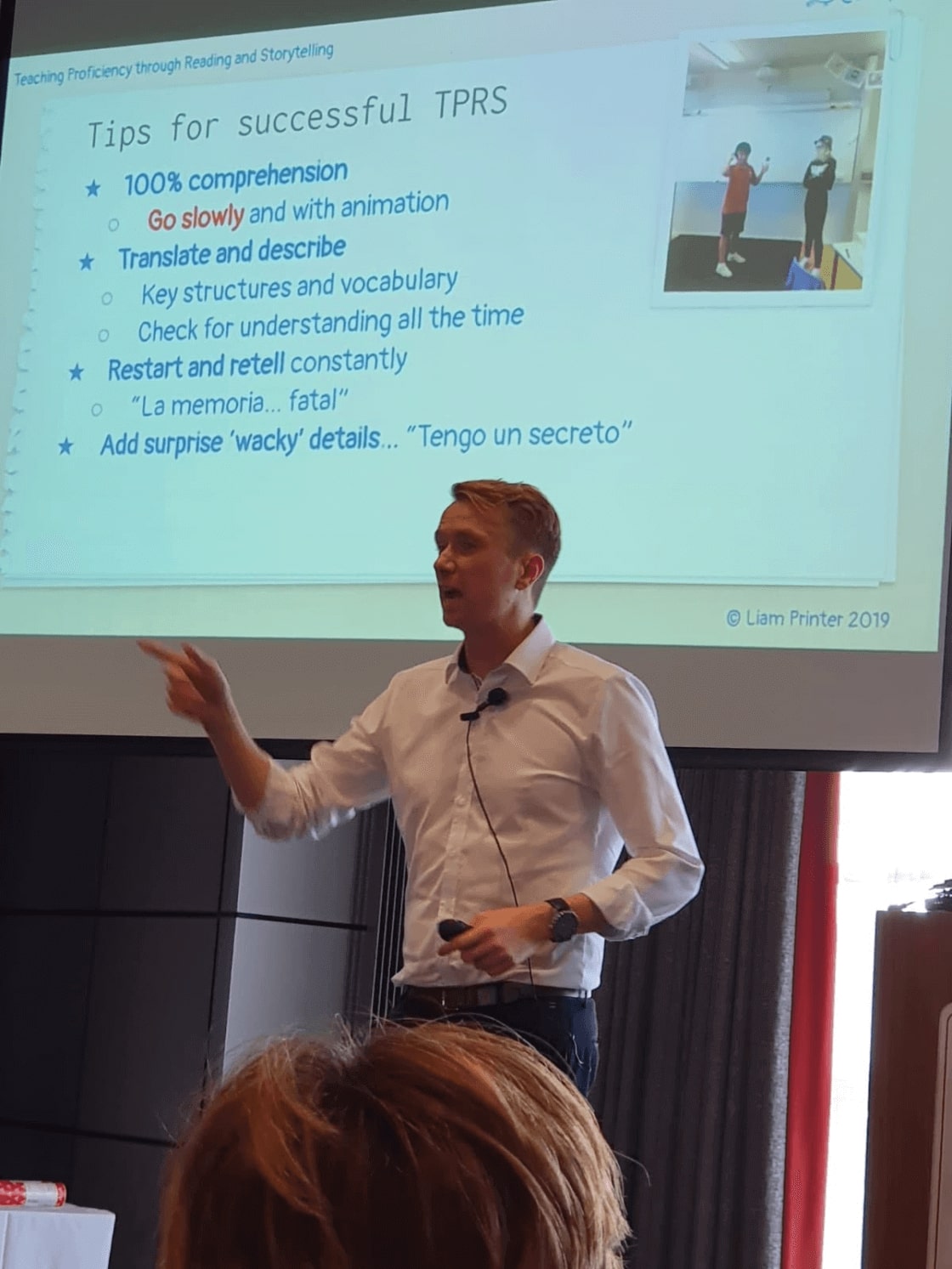

Below are some examples of my Spanish Year 9 students 'timed write' from April this year. This is a mixed ability class (no high/low sets or streaming) of students who were mid way through their second year of Spanish with me. They are 13-14 yrs old and in total have had 1.75 years of Spanish. Each week they have four 45 minute lessons of Spanish. After one week of doing a TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) co-created story with them, at the end of the fourth class class I asked them to write as much as they could remember of the story in 5 mins. They had no prior warning, no studying beforehand, no memorization tasks, no drills or worksheets. They had just been immersed and involved in the story creation for a week with me. The story is typically 'asked' in short 5-10 minute blocks, then students will interact with it by drawing scenes and retelling them to their partner, answering questions from the teacher, miming scenes and discussing, reading back on it with images etc. Then the plot continues and they are intently listening to see what happens next whilst also providing ideas for the details in the story, as well as some of the more extroverted students are helping me by acting it out.

After exactly 5 minutes of writing their 'timed write', they stop. There is no correction of mistakes or individual feedback on this writing. Accuracy is not the goal. The goal is fluency, competence, proficiency and confidence. So, they just count the words to see how much they were able to write from memory of their own co-created story. They are often shocked and pleasantly surprised by how much they can write with no preparation. As the teacher, I read through them all very quickly, looking for common, collective errors and use these to inform my teaching for the upcoming classes. If many students have not mastered one of my key structures, then clearly they need more repetitions of it in the next class, more personalised questions about their lives, more inputs.

Although tempting to only post the 2-3 best examples (as I have done in the past!), for authenticity this time I selected a random range of 11 examples from a class of 24. Through this range of exemplars I wanted to show you how a story can be internalised, acquired and 'learned' by all students; how stories reach all learners and just those we consider most motivated or driven to succeed. For the Spanish teachers reading this, my target structures with this story were "siempre ha querido; nunca ha probado; aún no ha logrado" (has always wanted; has never tried; still hasn't achieved). While I have my skeleton script idea of how the story will progress, it was the students who contributed the names, places and details while acting it out. This raises their autonomy. They feel ownership over it. They feel they created it. They feel it is "their" story. So they remember it and can re-tell and write it with no prior practice activities. Sure, there are some errors. Of course there are. Accuracy and grammar form are not the goal here... but they are a very pleasant by-product of compelling inputs and intent listening! The goal is confidence, fluency, proficiency, enjoyment and motivation for Spanish. Worksheets and grammar accuracy can come later, once they have listened to and read loads of compelling, comprehensible, input first!

In these early stages, the first two years in particular, we do not need to 'drill' outputs for accuracy. It is the interesting, compelling inputs through stories that lead to the proficient output from all learners and not just some! There is a different, more engaging, more creative, more fun and more enjoyable way to get to the same end goal. Think co-creation, not regurgitation. Think autonomy, not monotony. Think engagement, not detachment. Think motivation, not examination.

What do you think? I'd love to hear your comments! Download the weekly episodes of The Motivated Classroom podcast to listen to more research based teaching discussions about raising motivation in the language classroom.

Enjoying The Motivated Classroom Podcast? Leave a quick review on Apple Podcasts or join me on my patreon page here. I'd love to hear from you. Get in touch on social media with your questions and comments using #MotivatedClassroom via the channels below:

- Instagram: @themotivatedclassroom

- Twitter: @motclasspodcast

- Facebook: themotivatedclassroom

After 22 episodes and over 670 minutes of content, The Motivated Classroom podcast is taking a short, but much needed, two week break! For those who have fallen a few episodes behind, this winter break gives you a chance to catch up on all those episodes that have been bookmarked in your podcasts app for the last few weeks of this crazy semester! Episode 23 with Adriana Ramirez, will be released on Friday 8 January 2021.. So not too much longer to wait!

As my first venture into the podcasting world, it has been a steep learning curve in creating, recording, editing and promoting the content… but all things considered, I’ve loved it! Unbelievably, the podcast has now hit a whopping 21,000 downloads since it began five months ago at the end of July. Mind. Blown. Never in my wildest educational dreams did I think it would have been listened to so many times so quickly. Of course, there is no way people would find and listen to The Motivated Classroom podcast without the help of all of you wonderful listeners. I am hugely grateful to all of you for liking, sharing, telling friends and spreading the word. I want to say a special thank you to the 15 people who have become patrons of the podcast on my patreon.com page. I am indebted to your kindness and really appreciate your generosity! I’ve enjoyed some lovely coffee and crisps thanks to all of you!

Episode One, “Motivation: What is it and how do we do it?”, remains the most popular episode of the series, recently passing 2000 listens on its own but I think my favourite episodes have been those where I had the chance to interview some of my heroes. I want to take a moment to share my deep gratitude with those educational icons and legends that joined me as guests on the podcast this series: Soukeina Tharoo, Joe Dale, Beth Skelton, Chloe Lapierre and Adriana Ramirez (episode forthcoming); Thank you for sharing your passion and in-depth knowledge with the listeners. I loved chatting to you all and I learn so much from you each and every of you, every time we talk. Go raibh mile maith agaibh!

When I started my Doctorate in Education back in January 2015, I guess some of my main reasons for undertaking such a monumental project were; to improve my practice, to learn more, to challenge myself, to engage with research and potentially to open some doors and potential career prospects. What I didn’t know or expect at the time, was that by the time I would be finishing it in late 2020, a major objective would be to somehow share and disseminate both my own research findings and those from other major studies that were impacting my classroom practice. I wrote some articles, presented at conferences and led workshops but it wasn't until a good friend said “you should start a podcast about all this stuff” that I felt like other teachers were genuinely beginning to benefit from the research I had done and read about. Now, after five months and twenty-two episodes, it is clear that so many teachers around the world are really connecting to the motivational research and it makes my day to read the messages and emails from people saying they tried some of the activities in class and the students loved it.

So, thank you, merci, gracias, danke, obrigado, dank je and go raibh maith agaibh 🙏! I’d love to hear what episodes you liked the most so drop a comment here, post on The Motivated Classroom facebook page, comment on the instagram post or tweet me with your thoughts! I look forward to recording and sharing more episodes of The Motivated Classroom with you all in 2021!

Like many of you I have been going through a period of introspection and reflection on practices in my Spanish classroom and how I ensure I am always striving to have equity, social justice and respect at the heart of my teaching.

During this period I've been trying to focus on reading and listening to other voices. Using 'Spanish' names in the classroom has come up in a lot and I'd love to hear your thoughts and advice on my reflections.

Up until now I've always provided a list of Spanish names and nicknames to students at the start of the year. They are free to choose one if they wish but do not have to. I must admit that I have strongly encouraged them to go ahead and choose one though. In hindsight and upon reflection I feel this was wrong. The last thing I want is for a student to leave their own unique identity or culture at the door.

I've provided this list and allowed students to choose a Spanish name for themselves in the past as a lot of my doctorate research is on motivation and engagement. The three pillars of building intrinsically motivated, self-determined learners are:

- Competence

- Relatedness/Belonging

- Autonomy

The goal for students choosing their own unique Spanish name or nickname for our 'Españoland' class was always to build a sense of belonging and community to our class, whilst also providing them with the autonomy to choose whichever name they preferred, or what they felt they identified most with. After doing this for the past seven years, I'm quite convinced that this strategy does build a very special bond to our class. Students smile and beam when I greet them with this name, like we have our little secret society in our class. At parent meetings, they'll proudly tell parents.. "No Mum, I'm 'Juan' in Españoland". If we watch something where 'their' chosen name comes up, they get very proud and say things like "él también se llama Juan!". If I use their real name in class, they'll say "Señor, soy Juan aquí, no John". They feel like they are part of the Españoland family, like they have a special bond and belonging. It really helps to build relatedness and relationships. It's motivating.

In addition, I've had students use this opportunity to choose a new name as away to explore their sexual identity. I have two girls this year, age 12-13, who both chose Spanish male names. I double checked with them that this is what they wanted and each girl, individually, told me 'yes, I've always wanted a boys name' or 'I feel much more like a boy so I want a boys name'. For me, this was great. They were openly using boys names with their classmates in what felt like a way to express to their peers 'I think I identify with being a boy' or at least were eager to explore this openly. All of these things lead me to believe that allowing students to choose their own Spanish name for our class is something positive...

But...

Is this strategy disrespectful, offensive or harmful to native members of the Hispanic community? Is this practice unwittingly forcing students to denounce their own unique culture and name, and replace it with a new one? I must shamefully admit, I had not fully considered this until recently. At this point, it is important to understand the context of our classroom. I am a white, Irish, male teaching Spanish in Switzerland to students in an international school from all over the world. In a class of twenty, there would be typically around 15+ shared languages. I rarely, if ever, have 'heritage' speakers in my class. The demographics of our school are mainly northern Europeans or white people (around 75%), with the remaining 25% from all over the world. We have a small community of black and ethnic minority students, around 5-10% in total.

I have lived in Spain and have family there but I do not identify as Spanish. I identify as an Irish man who teaches Spanish and lives in Switzerland. So I realise I need to listen and learn from the Hispanic community on this. When I was reflecting on all this, I was trying to find a way for me, as an Irishman, to understand why my South American friends in particular, are so against students choosing their own 'Spanish' name. They've explained to me that it is mainly due to the underlying links to Spanish colonialism. So to understand this, I tried to imagine what it would be like for me.... If I walked into a classroom in, let's say, Turkey, and there was, let's say, a French person teaching English to a group of international students... and they had asked all their students to choose an Irish name from a list for their class, how would I feel? As an Irishman, I think I'd immediately think... "Why can't they just use their own names?".. but I would also think, "that is really cool that they are learning Irish names like Sineád, Siobhán, Aoife, Caoimhín, Gearóid... it's great they are learning some Irish culture through our names"... but... if they all had traditional 'English' names like John, Sarah, Tom, Elizabeth, George, I would probably be quite taken aback and also quite resistant. Why? Because as an Irishman I have a deep understanding of the oppression that was forced upon Irish people by the British occupying forces. An oppression that lasted 800 years and tried desperately to eradicate the Irish language and all Irish sounding names, but the language and those names survived. So an English teacher from France asking his international school class in Turkey to pick 'English' names would not sit well with me, even though that teacher never meant any offense or disrespect. Similar to my South American friends, I think it would unwittingly trigger links to colonialism for me personally even though all they were simply trying to do was build community in their classroom. I do not mean any offense by this, or to be political. I am merely trying to empathise and understand the issue from the perspective of my South American colleagues. For me, rightly or wrongly, the only way I can attempt to understand it is through my own cultural lens of Ireland's history.

And I guess with that I come to some kind of conclusion... we make decisions that we feel are for the good of our class but sometimes we are unaware of the cultural connotations, especially, I would argue, when we are teaching a language (and culture) that is not our own. I frequently feel inadequate, an imposter, a fake, for teaching Spanish when I am not a native speaker as but this makes me all the more passionate to try and get it right. To teach all parts of the culture and the history, the good, the bad and the ugly. The awful things the conquistadores did to the indigenous people, to the beauty and wonder of the present day Dia de Muertos tradition and celebration.

So where does that leave us on allowing students to choose a Spanish name for Españoland?

With all I've read and listened to, I feel I need to change this practice. I would love to know your thoughts on this. Especially, those who come from a Hispanic community or tradition. Do you allow students to pick a Spanish name they like or identify with? Or should we maybe only provide a list of cute Spanish nicknames? Or has this practice in all its forms had its day and it's time we just leave it completely? I think it has.

There is one thing I am definitely done with. If students do not want a Spanish nickname, even one that occurs naturally through the year, there will be no pressure whatsoever from me to have one. In fact, I am determined to embrace, uphold and celebrate their own name, heritage and culture. This is what I should have been doing all along.

We’ve now had our first week of post-quarantine classes, back in our real classrooms, with real, live people around… yes, they exist and are not just avatars or thumbnails. Does it feel different? Yes, absolutely it feels different but it has to. The world is different. Life is different. Schools have to adjust. The Swiss federal government decided that the country was ready for students up to the age of about 15 to go back to schools from May 11th but with restrictions: only half the class could be present each day in order to allow for more spacing inside the buildings. So we have students coming in every second day. This is the part that feels the strangest as we are all essentially back at work but the school itself feels very empty as we only have half the students in on any given day. From May 25th we will be back to full classes again with the exception of the older students, who will remain with online learning until June 8th.

It has been challenging to try to provide meaningful learning experiences for children when you have half of them on a screen on your whiteboard and the other half in front of you. I certainly felt more tired and less happy with my teaching this week but I had to remind myself that this is so new for all of us. We never trained or dreamt of having to do something like this. Now is not the time for high expectations on our own shoulders. We are all adjusting; we are all fumbling through this. I had to remind myself that the focus now, more than ever, needs to be on happiness, inclusion and relationships. Many of the students themselves were also quite nervous and shy to get involved in class as they suddenly felt a lot more in the spotlight with only a smattering of their friends around for support. It is now that they need our support more than ever.

Luckily, I work at a school with fantastic leadership who had left no stone unturned in the preparations for us being back on campus: classrooms are spaced out, there are floor markings around the teachers desk, hand sanitisers in every classroom, one way traffic for the cafeteria, staggered end times for younger students, masks are available for those who want them, as well as some excellent and funny instructional videos for students before they came back… using teddy bears to show what social distancing looks like. The students have been great and understand the need to change their social behaviours but… and it is a big but, they are children. As soon as they are out of class, they are of course getting within a metre of each other. This is unavoidable. Official guidance from the Swiss government is that children do not need to socially distance the way adults do but that wherever possible we should use best practice and judgement to avoid them being in groups. So that is what we are doing.

My overwhelming feeling is appreciation and gratitude to be able to work at such a great school, that had us so well prepared for all this and to be back in my classroom, seeing my colleagues and my students faces again. My friends and fiancée are great of course, but I’ve really missed having people around who laugh at all my terrible jokes. Let’s be honest, none of us became teachers so that we could sit behind a computer all day on our own. Teaching is a people-centred vocation and I, for one, am delighted to see that all those wonderful people are the same as ever. There is no difference there.

The hardest part for me in all this is that so many of the fun things have been stripped out of our jobs: the spirit weeks, the year group events, the graduations, the theatre productions, the sports competitions, the field trips… That is the hard part. But if it’s like this for us, then imagine what it’s like for our students. We now have a duty to make our classes more engaging, more fun and more centred around our students’ own lives and personalities. They are coming to school and going to our classes… that is it. No socializing, no sports, no events. Now is the time to be brave, try out new approaches and do whatever we can to get our students smiling again. Ask them what they want to do, what they want to learn and how they feel their learning should be assessed. Start there. Can we reinvent our unit to satisfy the three basis needs of relatedness, autonomy and competence which are required for motivation to flourish?

Going back to school is different. And it will be different for some time. But the people are the same, great people who were there before all this. Put the ‘people’ at the centre of your planning. Lower the expectations on yourself, on your students and think about the people. If not now, when?

The large and ever expanding evidence base behind Self-Determination Theory tells us intrinsic motivation is fostered by meeting the three basic psychological needs: Autonomy, competence and relatedness.

This is true for students as well as for ourselves as teachers. Essentially as humans, we want to feel like we have some choice we want to feel like we can do it and we want to feel connected. Hit those three needs and you are developing intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation leads to engaging in a task voluntarily out of pure enjoyment, interest and excitement. This differs from extrinsic motivation where we might complete a task out of fear, or in order to benefit from a reward of some kind.

Plan to motivate

Think of something you really like doing… now ask yourself does it meet those three needs?

Let’s say you love reading: you get to choose the book, the pace you go at, the author etc.

Autonomy.Tick. ✅

You understand it, you feel like you’re in the story, you're learning about the characters or the topic, you get it.

Competence.Tick. ✅

You connect to the characters, or you love discussing the book with other avid reader friends.

Relatedness.Tick. ✅

You are intrinsically motivated to read. The same can be done for any activity you choose freely to engage in out of pure interest and enjoyment.

Now think about our last online lesson. Did we plan activities for our students that meet those needs? Probably not! Why? Because it is not easy! This online teaching stuff is a steep learning curve and most of us are just trying to keep our heads above water and not lose the plot entirely! I’m with you.

So… how can we transfer what we know about self-determination theory to the online classroom in order to maintain intrinsic motivation among our students and ourselves, as teachers? It can feel a lot more difficult to hit those three basic psychological needs from our own sitting room, without the smiling (and bewildered!) faces of our students in front of us. But with some modifications to our planning we can get there.

✅#RemoteTeaching Day #15:

— Dr. Liam Printer (@liamprinter) April 6, 2020

With many #langchat #teachers & colleagues starting #onlineclasses today, here are my Top 3 Tips after 3 weeks of this:

👨💻Let them see you

🕺Get them moving

⬇️Lower the expectations

If you find these videos useful, give it a 👍 or share. Gracias 🙏 pic.twitter.com/96Da3hfL4V

My top four tips for motivation

Here are my top four tips to keep the motivation up in the online classroom for students and teachers:

- Let them see you: If you are using video software for your classes, this is great. Smile, be silly, talk about what you are doing in this lockdown period, show them your favourite hat, or your new hairstyle. Whatever. Just be yourself and chat to them. This builds connections and maintains the relationships. If you are not allowed to use video software, then make a few short youtube videos like these ones. They don’t have to be public if you don’t want that but the kids miss you. They want to see your face. And unbelievably, they find the most mundane things about our lives super interesting. Remember, they think we don’t exist outside the school walls so showing them your favourite plant in your apartment can blow their minds!

- Get them moving: They are sitting all day… alllll day. Just as we are. So do activities that get them out of their seats. As language teachers this is a chance to give more comprehensible input: “Find me something small and green in your house, you have 1 minute” or “stand up, add these numbers and sit when you have the answer”. Or ‘Simon says’. Anything that gets them moving, keeps them engaged, keeps them listening to your input and builds relationships. Even better if you do the activity too. They’ll be smiling and giggling at you trying too. This also builds their competence as they are listening, understanding and following along. The competence is developed even further if you make a big deal out of the cool item they found, or awesome t-shirt they've on.

- Lower the expectations: Online teaching and learning is simply not the same as the real classroom. Lower your learning objectives. Actively take things out of your units & curriculum. This is the time to be creative and do cool new things. Don’t worry about ‘being behind’... Behind who?? Or behind what?? We are all in this together. Now is not the time to over-burden with loads of exercises. Focus on motivation, not examination. Plan your lesson with detailed steps. Then when you are done, take one step out. Put it in the next lesson. This helps their competence as they feel like they are making it to the end each day. What about those learners who want extension activities? No worries. Have some youtube links ready or some extra reading or even better, some creative project to work on.

- Open up the choices: Autonomy is not about going off on your own tangent every time. It is about choice, self-direction and having some say in where things are going. Ask the students to vote on the tasks for the next class, give them 3 or 4 options of ways to show their learning. Let them be creative and make videos about topics you are doing. Give them the creative license and autonomy and you will be amazed and what they give you back. Especially those quiet students who say nothing in the video chat sessions.

Keep the conversation going

I’m tweeting out a little 2 minute video every day (like the one above) with hints and tips that I have learned from online teaching. I am on that steep learning curve too but it’s great to share and get the conversation going. You can follow the updates here. Would love to know your thoughts!

Please leave your comments below!

#TogetherWeAreStronger #MotivationNotExamination